Autumn 2024 Review from the Field of Sustainable Investing

Welcome to the autumn 2024 sustainability review! The year 2024 has brought significant changes to the field of sustainable investing. EU regulations such as CSRD and SFDR, along with global sustainability trends, are placing increasing demands on companies and investors. In this newsletter, we cover current sustainability-related themes, including the development of ESG funds, the pressures on tech giants’ sustainability reporting, and the impacts of new regulatory frameworks.

Our Topics in Brief:

- Current developments in ESG fund capital flows, performance, and definitions. ESG fund capital flows grew in Europe but declined in the United States. Article 8 funds grew significantly, while Article 9 funds shrank. European ESG funds have increased investments in the defence industry following Russia’s full-scale invasion.

- Social factors have had a positive impact on returns. Research shows that companies with high rankings in social scores have outperformed their peers over the past 11 years. Human capital is a key factor in corporate success, and employee well-being has been shown to improve results. ISSB is mapping investor information needs related to human capital.

- The EU’s ongoing pursuit of better data. New directives and standards have entered into force, improving large companies’ sustainability reporting and directing capital towards low-carbon investments. The directive will also extend to cover pension foundations and pension funds. The coverage of sustainability data has improved, but the development of sustainability data sufficiency and reliability continues.

- EU defined naming criteria. The EU has set criteria for ESG funds to prevent greenwashing.

- “AI challenges tech companies’ ESG status,” new solutions are being sought. The growth of AI technology has challenged the ESG status of major tech companies, particularly in terms of energy consumption and emissions. Tech companies’ Scope 3 emissions have risen significantly, weakening the credibility of their net-zero targets.

- Experts’ note on the conflict of interest. Experts warn of a conflict between non-commercial emissions standards bodies and major tech companies. Tech companies are seeking to influence how their emissions are calculated and offset. The Science Based Targets initiative allows only limited offsetting, but pressure to revise emissions accounting rules is growing.

- ‘Carbon cowboys’ profiting from protected Amazon rainforest areas - a cautionary tale of offsetting. Problems have emerged in carbon credit markets in Amazon rainforest protection projects, where corruption and abuses have led to distrust. International rules for carbon credit trading remain inadequate. New joint models between governments and major corporations for combating climate change are, however, already being developed.

- How are carbon credit markets supposed to work? A brief description of the operating principles of organisations and individuals in carbon credit markets.

- A new example of corporate-government cooperation in combating climate change. Major international corporations commit to supporting the protection of the Amazon rainforest in Brazil. The agreement provides an example of how other regions can approach sustainable forest protection.

- New sustainability regulation is expected to have a positive impact on returns. Pension operators believe that sustainability regulation will benefit all asset classes in the coming years. Consideration of sustainability factors can create market winners and losers; central banks, among others, have begun to favour climate-friendly targets in their investments.

- Quantitative sustainability assessment of asset managers - is it time?

Current Developments in ESG Fund Capital Flows, Performance, and Definitions

According to Morningstar, net capital flows into ESG funds grew in Europe during the first half of 2024. Article 8 funds grew strongly through organic growth, while Article 9 funds decreased in size. Their combined assets represent approximately 61 percent of EU fund capital. In the United States, ESG fund growth was mostly negative. Fewer new ESG funds were launched than before. Only so-called transition ETFs, where target companies invest in the transition to a low-carbon economy, are clearly growing. Morningstar classifies a fund as an ESG fund if the fund’s rules clearly state sustainability objectives. The investment targets of these funds are often selected using a best-in-class methodology based on ESG ratings and risks.

European ESG fund investments in the defence industry have more than doubled following Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, as political decision-makers have called for a strong defence industry. The growth is partly due to the appreciation of companies’ market value. According to Morningstar, the share of the aviation and defence industry across all sectors is still small, at approximately one percent.

Social Factors Have Had a Positive Impact on Returns

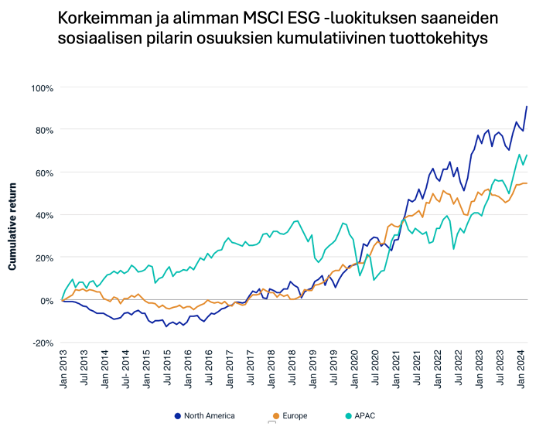

According to research published by MSCI in August, companies with the highest scores in the social pillar of MSCI ESG Ratings outperformed those with the lowest scores across all major geographical regions over the past 11 years.

Source: MSCI

Among social pillar themes, human capital was the most significant for companies - perhaps not surprising given the universal importance of employees to a company’s success.

The impact of employee well-being on company performance has been extensively studied. The American investment research firm Irrational Capital has developed a new way to select companies based on how happy their employees are at work. The Harbor Human Capital Factor (HAPI) ETF, created in partnership with Harbor Human Capital and tracking large-cap companies, selects companies with the highest human capital scores. Since its launch in October 2022, HAPI has outperformed over 90 percent of its peer funds.

Uniform data on social themes from companies is difficult to obtain.

That is why the IFRS International Sustainability Standards Board (ISSB) is launching a project to assess investors’ information needs regarding human capital-related risks and opportunities that can be expected to affect a company’s outlook.

The EU’s Ongoing Pursuit of Better Data

This year, the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD) and European Sustainability Reporting Standards (ESRS), applicable to large listed companies, entered into force in the EU. The deadline for transposing the CSRD into the national legislation of EU and EEA countries expired in July. Approximately 40 percent of EU member states and three EEA countries, including Finland, have either partially or fully transposed it into national legislation (source). In particular, SMEs acting as subcontractors for large corporations have complained about the volume of work required by the ESRS. Without this information, however, large companies cannot collect sustainability data from their subcontractors, which makes it difficult for them to make progress towards their own climate targets.

The CSRD also applies to occupational pension companies and large pension foundations and pension funds. For pension foundations and pension funds, its application begins from the fiscal year 2025, which will be reported for the first time in 2026. At that time, the EU’s Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation (SFDR) will also apply to supplementary pension institutions with certain limitations.

Under the SFDR and the EU Taxonomy Regulation, asset managers are required to prepare a standardised sustainability report for Article 8 funds that promote sustainability and Article 9 funds that invest sustainably following the ‘do no significant harm’ principle. Target companies of the funds are also required to follow good governance practices.

Thanks to EU and IFRS sustainability standards, the coverage of sustainability data from large listed companies has clearly improved, and sustainability regulation is generally expected to have a positive impact on return performance.

New EU climate benchmarks are directing capital towards low-carbon investments, as investors targeting net-zero emissions begin using benchmarks as the basis for their portfolios, and index products based on them become more common.

Alongside ESG ratings, more precise sustainability metrics reported by companies have emerged, which European and Europe-based listed companies must report with assurance this year.

Much work still remains to be done for the sufficiency and reliability of sustainability data. The GHG Protocol, an independent actor in emissions accounting, is updating its guidance, and global rules for emissions offsetting are still being developed.

EU Defined Naming Criteria

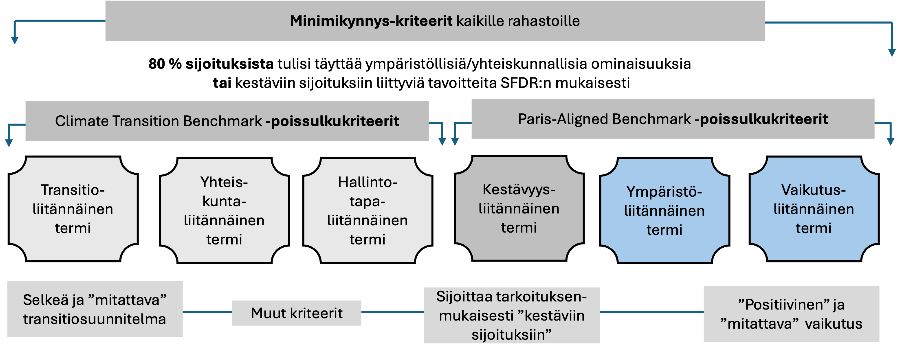

To prevent greenwashing, the European Securities and Markets Authority (ESMA) has published its final recommendations for ESG-named funds: classified into six different groups, as shown in the accompanying image. The image

According to the guidelines, the use of ESG/sustainable development terms in fund names also shows the recommendations for fund managers associated with each group.

The guidelines have two main requirements:

- Minimum investment threshold: At least 80 percent of fund investments must meet the social or environmental characteristics or sustainable investment objectives aligned with the fund’s investment strategy. Additional requirements are presented in the boxes in the image.

- Exclusion criteria: EU climate benchmarks Paris-Aligned Benchmark (PAB) exclusion criteria and Carbon Transition Benchmark (CTB). We will describe these in more detail in our next newsletter.

Source: ISS

’AI Challenges Tech Companies’ ESG Status,’ New Solutions Are Being Sought

Traditionally, ESG funds, which are largely index funds, have invested in large North American tech companies and have avoided fossil fuel industries.

Varma CEO Risto Murto stated on social media: ‘If you have a sustainability-focused fund, is it right that the fund’s largest investment is Microsoft. Without heavy tech companies, you’ve badly underperformed the indices, but now the AI boom is challenging ESG status. Data centres are energy guzzlers.’ We also covered this topic in our previous client newsletter, where we questioned the dominant position of large tech companies in ESG funds. The question became even more topical when tech companies published their 2023 sustainability reports, in which they reported significant emissions growth. These are Scope 3 emissions caused by, among other things, the construction of data centres for AI purposes. When a company like Microsoft has committed to net-zero emissions by 2030, there is considerable urgency to adopt renewable energy sources. One option to meet demand is even nuclear power. Microsoft recently announced its intention to invest $1.6 billion in restarting a nuclear power plant in Pennsylvania to meet AI electricity demand.

The US SEC was forced in March to soften climate reporting requirements for listed companies due to strong lobbying and dropped the requirement for listed companies to report Scope 3 emissions. The IFRS global sustainability reporting guidance, on the other hand, proposes that Scope 3 emissions should be reported, and the EU requires their reporting if they are material to the company’s business.

The International Energy Agency (IEA) has estimated that the energy consumed by data centres, cryptocurrencies, and AI will double from 2022 to 2026, reaching approximately twice Japan’s consumption. This growth threatens the viability of major tech companies’ net-zero targets. Microsoft’s emissions have grown by a third in three years and Google’s by as much as half in four years. A large portion of the growth is expected to occur in the United States, where many electricity grid areas still rely on fossil fuels.

Technology companies invest in renewable energy but cannot broadly control how polluting the energy used by their data centres is when they use the local electricity grid. Under current accounting practices, for example, energy consumed at night by a data centre in the coal- and gas-heavy state of Virginia can be offset by purchasing a certificate linked to solar energy during daytime in Nevada, which has a lower-emission electricity generation structure. Companies can offset energy use through investments in clean energy certificates, taking advantage of different US time zones in their emissions trading. These renewable energy certificates are significantly affordable in price.

For example, Meta reported net CO2 emissions of 273 tonnes last year, but the actual emissions from its own energy use are 3.9 million tonnes of CO2. On top of that come Scope 3 emissions.

The emissions impact of electricity used can, according to different accounting methods, be presented either by considering the actual origin of the electricity (location-based) or after the use of various market instruments (market-based).

Amazon considers itself a pioneer in green business. It reports having exceeded its self-set target of 100 percent renewable energy use. However, Amazon’s operations constitute a significant source of emissions, emitting relatively more greenhouse gases than its cloud computing competitors. In the article, University of Edinburgh Professor Matthew Brander compares the current offsetting system to a situation where one would buy from a physically active colleague the right to claim having cycled to work, while actually arriving by combustion engine car.

Experts’ Note on the Conflict of Interest

There is a risk of conflict arising between non-commercial actors responsible for creating corporate emissions standards and major tech companies, experts warn. However, the challenge to be resolved is how companies can achieve their ambitious climate targets.

Amazon’s principal owner Jeff Bezos’s foundation has a major influence

on the emissions reduction offset market. The foundation is a major funder of the Science Based Targets Initiative (SBTi). SBTi is the leading independent organisation for tracking corporate climate target commitments and progress, and is the most commonly used by financial actors in setting and monitoring climate targets. If companies that have committed to climate targets fail to meet them, they are removed from the SBTi registry.

Currently, SBTi allows limited offsetting of a company’s total emissions. If a company’s significant Scope 3 emissions represent 40% or more of total Scope 1, 2, and 3 emissions, they must be included in short-term SBTi targets. For example, Amazon has already been removed from the SBTi registry because it failed to meet its set emission reduction targets.

In the spring, as a result of lobbying, SBTi announced its intention to accept broader Scope 3 emissions offsetting. This proposal, however, did not pass because SBTi’s staff opposed it.

The current greenhouse gas emissions reporting framework is the non-profit Greenhouse Gas Protocol (GHG). Its carbon accounting rules form the basis for EU, SEC, and SBTi carbon accounting guidance. The Protocol is now considering revising its accounting rules - influencing these is also topical for companies.

Major tech companies are thus quietly seeking to influence how they must report their emissions. At the forefront are Amazon and Meta, which are pushing for the free use of the market-based offsetting described above. Google and possibly Microsoft do not support the current method either, but instead demand that the actual origin of electricity used by data centres be taken into account. Google has a data centre in Finland and Microsoft is building one in Finland.

Could one answer to Murto’s original question be that investors with climate targets should account for the emissions level in their Scope 3 target-setting and monitoring in accordance with IFRS sustainability standards, and that the rules of emissions offsetting should be stabilised globally, also taking into account the origin of electricity used? The greatest impact would come from establishing a unified pricing mechanism for emissions.

According to WTO Director-General Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala, there are 78 different emissions pricing and taxation mechanisms in the world. She announced in September that the WTO will take the lead in developing international emissions pricing together with the IMF, OECD, and the UN.

‘Carbon Cowboys’ Profiting from Protected Amazon Rainforest Areas - A Cautionary Tale of Offsetting

Over the past two decades, the new carbon credit financial commodity has become one of the world’s most important tools for combating climate change. Large multinational companies and organisations

that engage in voluntary carbon emissions offsetting have spent billions of dollars on them. Some of the offsetting has been directed at forest carbon sequestration. UN Secretary-General Antonio Guterres has now addressed this negatively, accusing offsetting of being corrupt.

The Amazon rainforest, which stores an estimated 123 billion tonnes of carbon, has attracted increasing numbers of carbon credit seekers due to its global environmental significance. These seekers have been called “carbon cowboys.” They have launched protection projects across the region and produced emission reduction credits worth hundreds of millions of dollars. The credits produced have in turn been purchased by major global corporations. The projects have helped transform the Brazilian Amazon into a largely unaccountable global centre for carbon credit trading, with sales valued at nearly $11 billion according to market research. According to the Washington Post’s investigation, more than half of the forest conservation carbon credit projects in the Brazilian Amazon have been carried out on government-owned land with an area of approximately 200,000 km2, or nearly two-thirds of Finland’s land area.

Brazil’s environment minister warned international investors in July against trusting the Amazon projects of carbon cowboys. A police investigation into the projects has now been launched.

The international community has failed to create clear global rules for forest carbon credits and their trading. In particular, opposition from environmental organisations against the commercialisation of nature-produced commodities has made it difficult to develop rules. Most trading takes place through voluntary market mechanisms, which partly explains the occurrence of abuses and corruption. Given the significant potential of forests and reforestation in combating climate change, it is unfortunate that the international community has not been able to make progress on this matter.

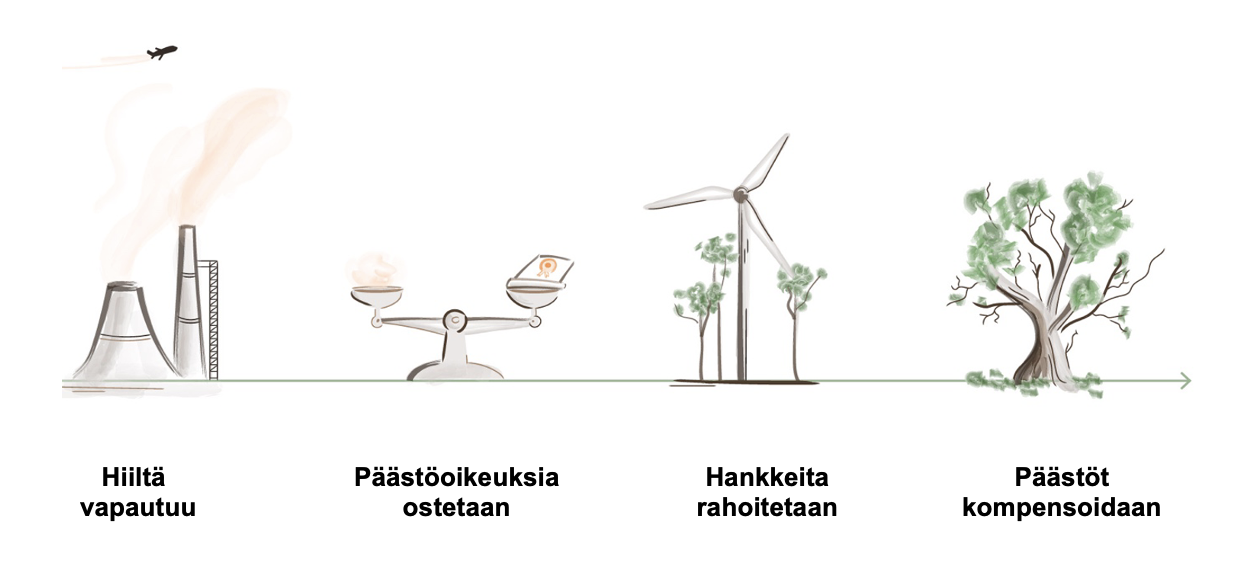

How Are Carbon Credit Markets Supposed to Work?

- Industry and transport release carbon dioxide into the atmosphere.

- Organisations and individuals can purchase emission allowances to offset or reduce their own emissions.

- Revenue from the sale of carbon dioxide emissions is used, for example, for certified conservation or reforestation projects.

- The aim of these projects is to reduce the amount of carbon dioxide by sequestering it in trees and soil. Certification organisations verify the emission reductions.

- Companies and individuals purchase these emission allowances, receiving an emission reduction certificate, i.e., a carbon certificate.

One of the key themes of New York Climate Week 2024 was emissions offsetting, which was supported by a group of major technology companies. They backed the model of former US climate envoy John Kerry, in which emissions offsetting would be implemented by directing financing to developing countries. Kerry, however, emphasised that companies should first focus on reducing their own emissions before beginning offsetting activities.

A New Example of Corporate-Government Cooperation in Combating Climate Change

The state government of Para, Brazil, together with Amazon (the company) and other companies and countries such as the United States and the United Kingdom, established

the LEAF Coalition forest protection initiative, which announced a deal worth approximately $180 million during New York Climate Week. Amazon and five other major companies committed to purchasing carbon dioxide emission credits to support the protection of the Amazon rainforest in the state of Para. The agreement is a positive step in protecting the world’s most important ecosystem and combating climate change, provided that the associated transaction costs remain reasonable. Carbon dioxide emissions are credited through this protection initiative.

The state of Para has suffered the most from deforestation since 2005. The state retains only the portion of credit revenue necessary to fund ongoing emission reduction activities. The remaining funds are distributed to local communities, including indigenous peoples. The purchase price of credits under the agreement is three times higher than the average price of previously used credits.

This agreement comes at a time when global demand for carbon dioxide emission allowances has slowed. However, major technology companies such as Microsoft, Meta, and Google have recently made significant investments in emissions offsetting in Brazil.

Although purchasing carbon dioxide credits alone does not solve the problems of deforestation, it highlights the critical role of companies in financing conservation initiatives. This new collaborative model provides an example of how other regions can approach forest conservation and climate action.

ESG Is Shedding Its Skin: Greenwashing Had Expected Consequences, but Sustainability Is Here to Stay

In the Financial Times expert interview ‘Who killed the ESG party?’, the recent history of ESG is criticised, during which asset managers and international service providers took a head start in product development and marketing before the emergence of EU and global

sustainability standards. At the core of the criticism are ESG ratings:

- DWS former head of sustainability Fixler: ‘ESG is a trillion-dollar marketing story’

- FT journalist Mundy: ‘ESG is a story of hype and ambition’

- Norwegian sovereign wealth fund head Tangen: ‘When we talk about ESG, we talk about the future of humanity. It’s about long-term thinking and thinking about long-term returns’

None of the interviewees doubted the importance of sustainability, particularly combating climate change. Neither did Warren Buffett, who has admitted that he underestimated the impact of climate change in his investments. Berkshire Hathaway faces a compensation claim of at least $8 billion for its infrastructure investment’s contribution to the Texas wildfires, because the company in question had not adequately prepared for them.

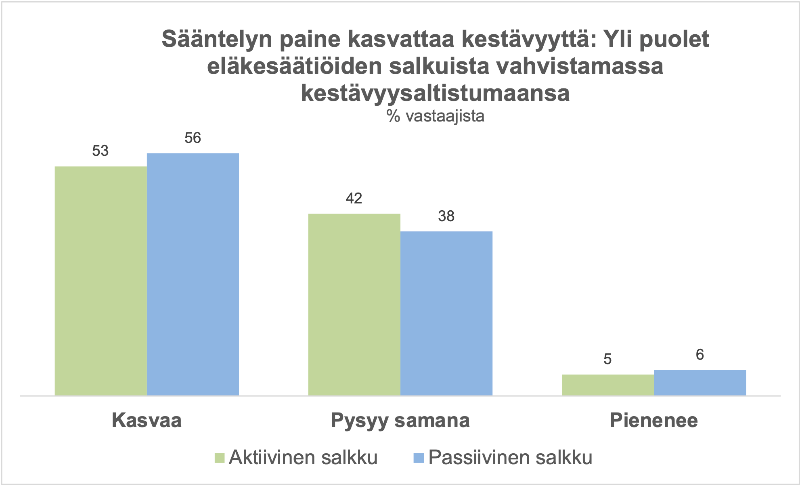

New Sustainability Regulation Is Expected to Have a Positive Impact on Returns

Investors are actively monitoring the energy transition, as a result of which the use of renewable energy sources in Europe now accounts for over 40 percent of total energy consumed. According to Think Tank Ember, it is likely that global greenhouse gas emissions began declining from 2023. An extensive study conducted among pension operators (involving 193 operators in 13 countries with combined assets of 193 trillion euros) shows that in over 43% of active portfolios, the share of ESG funds exceeds one-fifth. The corresponding figure for passive funds is 28%.

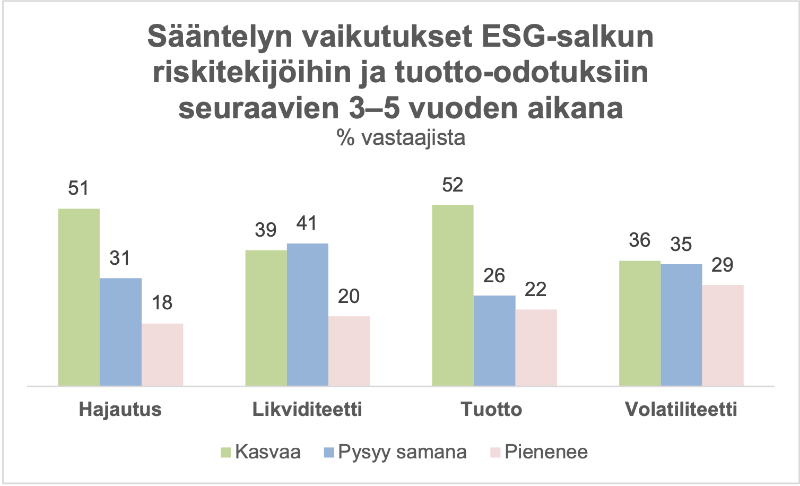

According to the study, over the next five (two) years, approximately 60% (approximately 40%) of respondents believed that all asset classes (listed equities and bonds, alternative investments) would benefit from new sustainability regulation.

Source: DWS

The main reason for growth, according to pension operators, is that the traditional way of investing according to modern portfolio theory does not adequately account for harmful externalities such as environmental pollution, biodiversity loss, etc. New sustainability indicators measure these sustainability factors.

ESG factors alone do not determine the return performance of an ESG fund. For example, when oil prices rise, they generally lag behind in performance because oil companies are typically excluded from them. On the other hand, rising interest rates can negatively affect cleantech companies because they are often dependent on the interest rate level, i.e., the cost of financing.

Generally speaking, the study reflects the expectation that ESG consideration can create market winners and losers:

- Government objectives and regulatory policy. Encouraged by voter demands, governments are increasingly focusing on addressing issues such as social injustice and climate change. As policy evolves to force markets to better reflect climate change-related externalities, the effects on corporate performance will likely be visible across all sectors.

- Sustainability data reporting. Both consumers and investors can make more informed choices.

- Consumer choices. Consumer attitudes and behaviour are changing rapidly, which can have implications for companies’ long-term profitability and market performance.

- Central bank policy. Central banks are increasingly adding green objectives to their mandates. They can promote these objectives by tailoring their balance sheet management to favour climate-friendly companies.

Quantitative Sustainability Assessment of Asset Managers - Is It Time?

The sustainability assessment of asset managers is predominantly qualitative. The key question is how sustainability, which is difficult to quantify, is taken into account in investment decisions. However, this can be examined more closely by investigating what data sources portfolio managers use and what their sustainability expertise is based on.

The basic prerequisite for investor institutions in selecting asset managers is signing the PRI commitment. The commitment requires asset managers to provide extensive annual reporting on how they have managed client assets. PRI charges asset managers a fee and provides them with a qualitative assessment of their work.

Concrete information about asset managers is now available thanks to new EU reporting requirements. Information can be found on, among other things, the number, quality, and performance of sustainable funds relative to other asset managers, as well as asset managers’ commitment to low-carbon objectives. The KPIs developed by IFRS for the asset management industry have brought concreteness to modelling.

The improved availability of factual information enables quantitative assessment of asset managers. At its best, the selection is based on the investor institution’s intent.

Development in the field of sustainability is rapid. We are all beginners. We will continue our message shortly, when we will focus strongly on the increasingly popular EU climate benchmarks. According to a recent FTSE Russell study, investors found climate benchmark-related regulation to be the most useful. We will also describe the structure of the SFDR standardised sustainability report and its application to cross-asset manager sustainability reporting as we understand it.

If our topics are of interest, please get in touch. Have a wonderful autumn!

Susanna Miekk-oja and the Tracefi team