Sustainability Newsletter Autumn-Winter 2023

Dear reader, climate change is accelerating and the need to achieve low-carbon goals is acute. However, US politics is making this more difficult, as Republican-dominated states oppose ESG investing. Although the unclear definitions of ESG and greenwashing associated with products have received justified criticism, this does not make sustainable investing a failure. On the contrary, criticism can guide towards clearer and more precise definitions of sustainable investing.

The dilemma for investors pursuing low-carbon goals is that investments in renewable energy have yielded less this year (1 Jan - 31 Oct) than investments in fossil energy; the renewable energy index has lost over 40% to the oil and gas index. The main reasons are wars and high interest rates, which have raised financing costs for renewable energy projects. Defining and evaluating sustainable investment is difficult, and results are hard to compress into a few figures.

Finally, the sustainability data required from financial actors and the sustainability data reported by companies are converging. Starting from 1 January 2024, the European Sustainability Reporting Standards (ESRS), which apply to large listed companies, require companies to report the adverse sustainability impacts needed by financial actors and the measures taken to promote sustainability. The IFRS’s new global climate standard and general sustainability reporting principles published in the summer are compatible with ESRS and harmonise sustainability reporting outside Europe.

Sustainability standards are a foundation of reliability the likes of which has never been experienced before. But reporting alone does not direct funds to sustainable targets — rather, it is how investors adopt the information and use it in their own decision-making.

Our topics:

- Webinar ‘Creating Added Value Through Sustainability in Emerging Markets’

- A Major Shift for Investors: From ESG Ratings to Sustainable Investing

- ESG Ratings Under Scrutiny

- Choosing Carbon Metrics and Targets on the Path to Net Zero

- A Historic Phase in Sustainability Reporting

- ‘What Do You Actually Do at Tracefi?‘

Webinar ‘Creating Added Value Through Sustainability in Emerging Markets’

Anna Hyrske, leading sustainability expert at the Bank of Finland, along with experienced portfolio managers Antti Raappana from S-Pankki and Joni Leskinen from Titanium, discussed the new role of the Global South in balancing between the West and the East. Click here for the recording.

A Major Shift for Investors: From ESG Ratings to Sustainable Investing

Debate Over Principles in the USA

‘I will never use the term ESG again,’ declared Larry Fink, CEO of the world’s largest asset manager BlackRock, in June. He cited the politicisation of the concept as the reason — there is resistance from both the far right and the far left. BlackRock continues to take ESG into account by investing in fossil fuel companies if they have a credible transition plan. As an asset manager, BlackRock aims to have 70% of its managed corporate assets committed to the Paris climate goals on a net basis by 2030.

Republican politicians are now branding ESG as a liberal agenda. According to them, asset managers who emphasise it are making return-seeking secondary. The accusations have led pension actors in certain states, such as Texas and Florida, to remove ESG-focused asset managers from their roster. The accusations are particularly directed at ESG raters and have led to significant redemptions from ESG funds managed by those asset managers. Additionally, an employee of a major American company has filed a lawsuit claiming that the pension fund has underperformed the market return by investing in

ESG funds. Other pension funds are closely following the progress of the lawsuit.

This is simultaneously testing the effectiveness of traditional ESG terminology. Due to Republican pressure, US President Joe Biden used his veto power for the first time during his term to prevent the banning of ESG investments in the country’s pension funds. Biden has cited risk management as the reason. The election of climate change denier Mike Johnson as Speaker of the House is unlikely to ease Republican opposition to ESG.

Political pressure has led to the following:

- The asset managers’ alliance for cutting emissions (Net Zero Asset Managers initiative, NZAM), as well as the UN-backed joint commitment of major European insurance companies (Net-Zero Insurance Alliance, NZIA), are fracturing due to fear of legal consequences.

- American credit rating agency S&P has stopped attaching ESG scores to the creditworthiness assessments of debt investments, partly because users felt the scoring provided no real benefit. It is indeed impossible to distil a multidimensional subject into a few figures.

The contradiction of the topic is illustrated by the fact that Republican-supporting regions dominate the US clean energy technology boom, having already received approximately 80% of all clean energy and semiconductor projects supported by the federal green transition support programme IRA (Inflation Reduction Act). Major oil companies (Exxon, Chevron) are receiving funding from the US’s massive green transition support programme IRA (Inflation Reduction Act) for carbon storage projects and have simultaneously announced new investments in oil production. It is therefore not easy for investors to decide whether to exclude oil producers from their portfolio. According to the IEA, oil and gas producers have globally invested only one percent of green energy investments, and last year they allocated 2.5 percent, or 20 billion dollars, of their capital to the sector. These matters are being discussed at the UN COP 28 climate conference starting tomorrow in Dubai.

Major asset managers have been seeking a solution to transfer ESG engagement to investors. Now BlackRock, Vanguard, State Street and Charles Schwab are piloting the transfer of engagement to individual investors as well, gradually shifting the responsibility for the impact of assets to their owners. Investors are given various options to choose from: leaving decision-making authority in the investment target to the company’s board and shareholders according to their proposals; to the asset manager at its discretion; according to an ESG perspective; or even according to Catholic values.

The EU already mandated a year ago that investor clients be asked about their sustainability preferences before providing investment advice. Responsibility for the impact of investments is gradually shifting to the investor client.

The US financial regulator SEC is taking asset managers to court for false ESG marketing communications. Deutsche Bank’s asset management company DWS agreed to pay a fine for misleading statements regarding ESG investments and recommendations. The process lasted two years, during which DWS’s share price fell by 20%. Authorities in other countries have also tightened their actions.

A Practical Fund Example

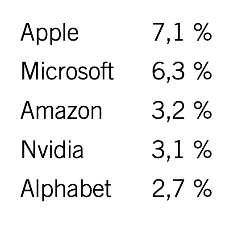

BlackRock’s iShares ESG Aware MSCI USA is one of the world’s largest ETFs. The fund has a high MSCI ESG rating (AA). The fund’s investment criteria include the exclusion of oil and coal production. The top holdings of the fund consist of the most well-known large technology companies, which, however, are hardly in a decisive position to save our planet:

The fund’s name contains the term ‘ESG-aware’, which is why many may perceive it as an ESG fund. The investment selection is based on a best-in-class methodology, where targets are selected based on ESG ratings while excluding critical sectors. However, many who invest in ESG funds want their money to contribute to promoting environmental and/or human well-being. In September 2023, the SEC announced it would require that fund names correspond to 80% of their investments.

In the best-in-class methodology used particularly in ESG index funds, the investment universe is first determined based on ESG criteria, and then financial analysis is applied. This leads to sub-optimisation and may be one reason why the method has lost some of its appeal. Now, deeper sustainability data has become available in addition to ESG ratings. Source.

ESG Ratings Under Scrutiny

Despite criticism, ESG ratings are important for companies, asset managers and investors alike. Many institutional investors limit their investment targets not only by credit rating but also by sustainability rating. The EU is developing the classification and supervision of ESG raters by requiring detailed descriptions of rating methodologies. As is well known, different ESG raters use different methodologies. For example, FTSE Russell uses 300 indicators in its assessment, while S&P utilises up to a thousand indicators.

Ratings differ considerably from one another. According to researchers, there can be various reasons for the problems and differing results: Conflict of interest — investors pay for ratings, but at the same time raters advise companies on how they can improve

- their ratings. Raters’ differing opinions. For example, some assess the materiality of a company’s impact, such as pollution based on ecological harm. Others focus on the financial significance of ESG factors, considering pollution only if it causes costs to the company.

- According to research, up to half of the differences in ratings are due to data discrepancies.

As a solution, researchers recommend using multiple ESG ratings simultaneously.

The Difficulty of Defining Sustainable Investment

Relying on ESG ratings alone is not sufficient in pursuing sustainability. Research by Scientific Beta has shown that companies with high ESG ratings produce just as many emissions as companies with low ESG ratings. ‘The correlation between ESG rating and carbon intensity is virtually non-existent,’ says research director Felix Goltz. EU legislation has set criteria for how asset managers must report on the sustainability of investment funds. However, the EU’s ambiguous and inconsistent definition of sustainable investments has recently caused confusion in the financial industry.

According to the EU, a fund is sustainable if its investment targets:

-

promote environmental and social development,

-

follow good governance practices,

-

and do not simultaneously cause significant harm (DNSH).

A fund is considered to take into account or promote sustainability if it promotes either environmental and/or social characteristics.

The EU’s justification for the loose definition of sustainability is that it is not the EU’s role to create standards. It has classified funds into Article 6, 8 and 9 funds, where Article 9 means the fund aims to make sustainable investments and Article 8 means the fund takes sustainability into account in investment decisions. In Article 6 funds, sustainability is not taken into account, although the asset manager must justify why sustainability factors are not relevant to the fund.

The EU refined its definition at the beginning of 2023 so that each Article 8 and 9 fund must state how much they invest sustainably at minimum. The question still open is whether the share is defined on a revenue-weighted basis, i.e. only the portion of investment targets’ revenue that promotes sustainability goals is included, or using a ‘take it or leave it’ approach, where a company is considered entirely sustainable if even a small portion of its revenue supports some sustainability goal. ETF funds in particular can therefore be Article 9 funds if their investment targets pursue sustainability (for example, committing to the Paris climate goals), even if not all of the fund’s investments are sustainable.

The EU’s article classification will be refined and transparency requirements in fund reporting will strengthen. More detailed guidelines are expected by the end of the year, but at the latest when new Commission members begin their work. Practical advice: when you want to assess a fund’s sustainability, evaluating the fund’s ten largest investments already tells a lot.

Just as ratings alone are not sufficient, neither are different articles sufficient for promoting the sustainability of investments. This happens by reducing adverse sustainability impacts, where the metrics are both the mandatory and voluntary adverse impact indicators of the EU’s Disclosure Regulation, and by promoting sustainability impacts, where the metrics are taxonomy eligibility and alignment shares (relative to revenue, CAPEX and OPEX). The Taxonomy Regulation is incomplete — it lacks the assessment of social sustainability impacts. The aforementioned metrics are also the same ones that companies will soon be required to report by law.

The number of adverse impact indicators will increase so that financial actors must report ever more broadly on greenhouse gas emissions related to their operations: targets, storage, removal, emission units and progress in reducing emissions.

Large Finnish pension companies are not subject to the EU Taxonomy Regulation’s reporting obligation (excluding real estate). Instead, they have set growth targets for a so-called climate portfolio, which they monitor.

Examples of New Types of ESG/Sustainable Funds

‘Try to solve everything you can without producing any carbon emissions at all.’ - Bill Gates

Investors are now looking for funds composed of ‘emission improvers’, i.e. companies that are reducing their emissions and offering low-carbon solutions. Previously, the strategy was based on excluding the largest emitters, but this is not a solution, as the majority of emissions are concentrated in only a few sectors which, according to Bridgewater Associates, produce over 90% of listed companies’ and 60% of global emissions. Mere exclusion is therefore not a solution for removing carbon in the real world.

Instead, what is of interest are climate-linked indices that, for example, rely on measures aimed at carbon removal. According to Microsoft co-founder Bill Gates, amazing climate technologies already exist — the challenge is how to make them work. His founded Breakthrough Energy Ventures is already raising its third billion dollars for companies focused on mitigating climate change. Targets include an American green electrolyte producer, a green cement producer and a company focused on freight battery technology. Gates is cautious about carbon capture and storage as a broader solution: ‘It’s always going to be expensive, and you can’t use it at scale to reduce emissions. We really have to admit that this is a world of limited resources. And one thing that is magic in this world is innovation.‘

Choosing Carbon Metrics and Targets on the Path to Net Zero

We are accustomed to assessing interest rate and P/E ratio levels. But emissions metric concepts and calculations are new to financial actors and require in-depth study to understand whether metric values are high or low. PCAF (Partnership for Carbon-Accounting Financials) defines the following as key means to mitigate climate change and achieve the Paris climate goals regarding emissions from investments:

-

reduction

-

avoidance, such as the use of renewable energy sources, and

-

removal, such as injecting carbon dioxide underground. Emissions reduction monitoring is based on Scope 1, 2 and 3 reporting.

Scope 3 emissions are indirect emissions from an organisation’s value chain, which often constitute the largest share of an organisation’s total emissions. For example, in the financial sector, these emissions can account for over 80%. The technology companies in our fund example do not accurately report Scope 3 emissions, although Apple, for instance, has reported that Scope 3 constituted 99% of its 2021 emissions.

Esa Saloranta, portfolio manager of the eQ Blue Planet fund, who spoke at the Finsif annual seminar on 16 November 2023, stated that ‘Scope 3 is one of the most important signals that tells about a company’s ambitions, covering the supply chain all the way to end-product or service innovation’.

In September, a law was passed in California requiring companies to report these emissions by 2027. Apple, among others, supports the law.

Three Essential Questions for Investors

There are three important questions related to defining greenhouse gas emission targets:

-

To what date is a possible net-zero target tied, and what are the interim targets?

-

Does the emissions reduction target cover all emission scopes (Scope 1, 2 and 3)?

-

What carbon metrics are chosen? The risk of double counting is one justification institutional investors use for not having reported Scope 3 emission data. Collecting such data is particularly laborious from banks’ loan portfolios.

The EU requires large listed companies to report all emission scopes if they are material to the company, and gave companies an extra year to begin Scope 3 reporting if the number of employees is below 750. IFRS requires reporting of all emission scopes but gave companies an extra year to begin Scope 3 emissions reporting. Service providers (including MSCI, Sustainalytics) report companies’ Scope 3 estimates until auditor-verified data is obtained from companies for the year 2024.

A fourth essential question is what share of the portfolio is allocated to the climate portfolio, i.e. solutions pursuing low-carbon goals.

Differences in the Information Value of Metrics

The most commonly used emission metrics are:

- Financed emissions

- Carbon footprint relative to invested capital (tCO2/MEUR)

- Carbon footprint relative to the target company’s revenue

In addition, attention is paid to the applicability and coverage of carbon data.

Relative emission metrics allow comparison of investments within different asset classes. Setting targets can be challenging due to many factors. Asset managers often favour carbon intensity in their reports, where financed emissions are compared to the investment target’s revenue. Although this metric is easy to calculate, it is best suited for situations where companies in the same industry are compared. This is deceptive during periods of inflation, as the direction of development changes when inflation drives revenue up and emissions begin to decline relatively.

PCAF recommends financed emissions and carbon footprint

relative to invested capital as metrics for investors. Financed emissions are the most reliable and concrete metric for measuring emissions in each asset class. In pursuing carbon neutrality, it is precisely this that must approach zero. Varma announced last year that it is the first in Finland to set concrete targets for financed emissions.

Institutional example: New joint investment criteria for the pension funds of four German states:

- equity investment benchmark aligned with the Paris Climate Agreement (PAB)

- bond and equity investments aligned with the EU taxonomy and UN Sustainable Development Goals

- commencement of monitoring companies’ Scope 3 greenhouse gas emissions

The tightening led to approximately one-fifth of the eleven-billion-euro investment portfolio having to be replaced.

A Historic Phase in Sustainability Reporting

The EU’s Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD) sustainability standard and the global IFRS sustainability standards are finally coming into use. Starting from January 2024, sustainability reporting will rise alongside financial statement information and will be verified by auditors. The sustainability report is based on the ESRS sustainability standard and covers:

- sustainability risks, i.e. financial impacts (risks and opportunities), and

- sustainability impacts related to the environment and climate, social responsibility and good governance.

The IFRS sustainability reporting organisation ISSB published two global sustainability standards S1 and S2 in June, covering general principles and the climate standard respectively. IFRS uses the global SASB sustainability standard, which it has acquired, as the foundation for its standards.

Tracefi licensed SASB as early as 2017, the first in the Nordics, to utilise it for sustainability reporting for institutions and asset managers, describing, among other things, financially material sustainability risks and opportunities.

ISSB is the global baseline for various regional reporting frameworks, such as the EU’s ESRS. Thus ESRS and ISSB complement each other. Example:

Source: PwC

Source: PwC

The change is truly significant:

-

Standardisation enables global comparability, so financial actors gain the ability to compare investment targets and allocate capital to sustainable targets

-

Detail improves usability, as clearly defined sustainability data is digitally available more broadly to various stakeholders for decision-making

-

Assurance increases reliability, as the company’s board is responsible for the data and the auditor verifies the accuracy of the information. The quality and reliability of sustainability data rises to the level of financial statement information.

Additionally:

-

The US SEC is currently finalising climate reporting guidance that requires listed companies to report Scope 1 and Scope 2 emission levels, as well as Scope 3, if it is material to the company or part of climate targets. Investors support the proposal and companies oppose it. It will be interesting to see the final outcome.

-

Starting from 2024, the 250 largest companies in India must also obtain assurance for their ESG and supply chain reporting.

-

Sustainability reporting is of interest not only to India but also to China, as the mapping of Western companies’ Scope 3 emissions affects the business of companies in their subcontractor roles.

‘What Do You Actually Do at Tracefi?’

asked a pension sector representative when we met in the summer.

I explained what we do in practice: sustainability assessment of institutional investors’ portfolios. Fact-based, in accordance with laws and guidelines, in-depth. Today I would answer differently, as Stanford University ecology professor Gretchen Daily put our goal into words better than I could. I quote:

Although nature is the foundation of everything, technology, urbanisation and the global division of labour have blurred people’s understanding of what keeps them alive. Whether it is sad or not, the significance of money is understood more broadly than the significance of nature. My mentors told me that appealing solely to respect for nature will no longer save us. The majority of people live so disconnected from it.

At Tracefi, we strive to find the sustainability trace of investments, its development and its impact on results. Well-considered sustainable investing principles integrated into the investment plan create a roadmap for investors towards performance that is also sustainable.

Meeting you on behalf of Tracefi

Susanna Miekk-oja