Summer 2022 Newsletter

Dear fellow follower of sustainability developments, our letter is longer than usual, partly due to the impact of geopolitical events and the timing of several regulatory deadlines in this period. The topics of this newsletter are:

- Sustainable investing and the inconvenient truth

- Regulatory progress and tightening globally

- Intensified supervision targeting ESG raters, asset managers and banks

- Models for combining value creation and ESG

- How to practically direct investments to sustainable targets?

- Summary and news from Tracefi

Sustainable investing and the inconvenient truth

‘Isn’t Finnair an unethical company because it serves alcohol on its flights?’ was a typical question twenty years ago that one had to answer for clients. As a mathematician, I already longed for concreteness and measurability in sustainability back then. A sustainable fund attracted only mild interest between 2004 and 2016, mainly from those who wanted to make a difference. It was only from 2019 that the era of ESG investing began — investing in companies that take ESG into account. It was seen as a way to improve the world and achieve superior returns. Now ESG is under attack, and it is interesting to see how broad the front of ESG opposition is.

Fifteen years ago, Al Gore’s documentary An Inconvenient Truth, depicting the effects of climate change, brought biodiversity loss into general awareness. The documentary was shown as invitation-only screenings around Finland by my then employer. Gore is now one of the founders of Climate Trace, a company that creates real-time emissions tracking tools for investors so they can see where and which companies cause the most emissions — data access will be free for users. Gore’s film had a major impact in raising awareness of the topic and led to strong growth in the ESG field.

Now it is up to us, the actors in sustainable investing, to answer our own inconvenient truth questions and move forward, as the climate crisis and inequality have worsened since Gore’s documentary was released. The criticism directed at ESG investing is credible and strong. Its core sources are:

-

Return performance: The underperformance of ESG funds this year (after 10 years of outperformance), due to Russia’s war of aggression. Energy companies and the defence industry, whose valuations have risen sharply, have been underweighted in ESG funds. Now European funds, which represent over 80% of ESG fund assets, are gradually adding shares from these sectors, as energy companies are seen as promoting the transition to low carbon.

-

Classification of gas and nuclear power as sustainable energy sources by the EU. What has received less attention is that the conditions for classification are strict.

-

Politicisation: Criticism of ESG investing by the U.S. Republican Party. The Republicans’ opposition targets in particular asset managers that exclude oil companies, ESG raters, and asset managers more broadly, as they are seen to be profiting from ESG.

-

The backdrop was set by a speech by HSBC’s head of sustainability, Stuart Kirk, in which he claimed that climate change is not a risk for investors and asked: ‘Who cares if Miami is 6 metres underwater in 100 years?’

-

Mike Pence claims in his opinion piece in the Wall Street Journal that an ESG strategy would be harmful because it allows the left to achieve what it can never hope to achieve in a free market. Pence added that the next president should ban the use of ESG principles nationwide.

-

ESG is even expected to become one of the themes in the U.S. November midterm elections. In conservative states, including Texas, anti-ESG legislation is already pending. West Virginia Treasury has ended its cooperation with, among others, BlackRock and J.P. Morgan, as they have been alleged to be boycotting energy companies. The oil and gas industry is one of the most important business sectors in the state.

-

-

With Republican Party support, the Supreme Court has decided to strip the nation’s top environmental authority, the EPA, of its ability to limit greenhouse gas emissions from power plants. It is feared that it will also oppose the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) proposed corporate climate reporting rule.

-

As a new counterforce to Republican advances, the Democrats pushed through the ‘Inflation Reduction Act 2022’ in the Senate on 7 August, which includes a massive climate and healthcare legislative and funding package that could improve the Democrats’ position in the midterms.

-

Greenwashing allegations: Asset managers are accused of portfolio managers not genuinely taking sustainability into account in their investment decisions, but outsourcing research to rating agencies.

-

Over-marketing of ESG in corporate business.

-

Conflicting ESG objectives: ESG cannot be bundled into a single acronym to which scores are assigned. An example is environmental and social factors, whose number and weight of descriptive indicators are in completely different leagues.

- According to The Economist’s cover story (21 July):

-

ESG lumps together a set of goals and does not offer a coherent guide for investors and companies to make the inevitable trade-offs in society.

-

The acronym should be torn apart and only the E emissions metric retained.

-

- According to The Economist’s cover story (21 July):

Critics rightly demand strengthening the role of governments relative to corporations. Despite the criticism, at least in Europe, interest in passive sustainable investment funds has been greater than in other ETFs through the end of the second quarter. Demand may be reinforced by the EU statutory guidance that came into force in early August, requiring investment advisors to ascertain clients’ sustainability-related priorities in addition to financial objectives. The weightiest criticism has been that ESG lacks reliability and measurability. Regulators and standard-setters have been working to fix this.

Regulatory progress and tightening globally

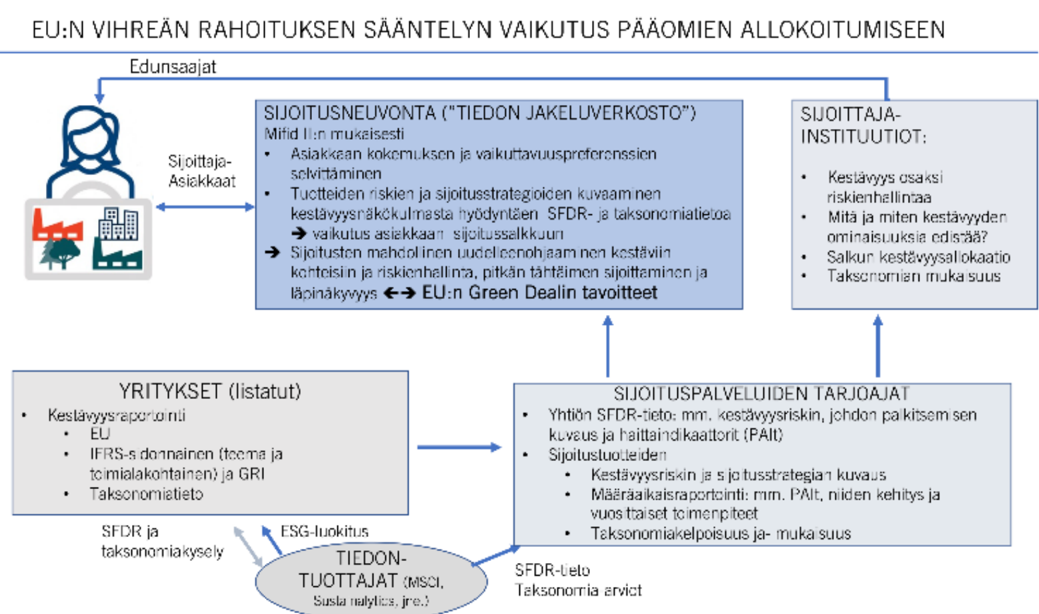

The EU is now the frontrunner in developing green finance legislation and guidance. Below, I have attempted to broadly describe the content of its regulation for allocating capital to sustainable targets.

Three different models for sustainability reporting

In sustainability reporting, it is no longer believed that market forces will define the standards themselves, because there is no need for regulated reporting. Instead, it is recognised that, as in financial reporting, regulators are needed to create standards and enforce their use.

We are now in a situation where three significant new climate reporting proposals are or have been open for public comment: the rule proposed by the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC). The essential difference from the EU proposal is that the reporting obligation does not extend to listed companies’ Scope 3 emissions (definitions here) unless they are material to the company. The SEC has also proposed new reporting guidelines for ESG funds.

The proposal of the International Sustainability Standards Board (ISSB). There were over 1,300 commentators, including Saudi Central Bank, Temasek, and Burberry. Three doubts rose above the rest: extending reporting to companies’ broadest emissions metric, Scope 3 (in the UK, two out of three premium companies already do so); putting developing and developed markets, as well as small, medium, and large companies on the same footing in reporting requirements. The decision on the content should be ready by the end of the year.

A global sustainability standard is now being created as the SASB standard evolves into the IFRS Sustainability standard (link to abbreviations). The IFRS standard, which is the global financial standard for listed companies, has been developed over about twenty years and enacted into legislation in various countries. The IFRS Sustainability Standard is only a first draft and is not yet mandatory for anyone. Mandatoriness will arise when the standards are ready and enacted into national laws in different countries. The EU and USA will certainly act most quickly.

The IFRS sustainability standard will be both theme- and industry-based, but above all investor-oriented. Tracefi has been a SASB standard licensee since 2017, because we believe in facts and transparency. We have not yet chosen ESG ratings as the basis for sustainability analysis, because what a company has not reported itself has hardly been hard fact.

The European sustainability reporting standards (ESRS) developed by the European Financial Reporting Advisory Group (EFRAG), including ESRS E1: Climate change (13 standards in total), were open for comments until 8 August 2022.

It is clear that investors’ fear is that with three standard proposals, they will remain separate. I listened to three different regulatory bodies in a joint panel: the message was clear: they are working together and seeking to synchronise, with the IFRS standard serving as the basis for the EU standard. In the United States, however, politics will still determine the outcome. For now, efforts are focused on listed companies, starting with the largest, but the then SASB representative pointed out that SASB metrics can also be applied to smaller companies already. We have also done this in risk assessments for clients’ private funds.

Focus on the social dimension

In July, the Platform on Sustainable Finance working group published a review with recommendations on the current state, metrics, and interpretations of the Social dimension:

-

At the core of everything are the social responsibility Minimum Safeguards (MS) criteria, as described in Article 18 of the Taxonomy Regulation. This article guides EU social responsibility legislation on the corporate side, the results of which are summarised in investor-side reporting.

-

The EU Commission is currently developing two important directives directly related to MS:

-

The Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence (CSDD) directive will make human rights due diligence mandatory for larger EU companies, while

-

The Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD) will require the reporting of human rights due diligence information by EU companies. Neither regulation will likely make it in time for the next reporting cycle for smaller companies, but they are estimated to be in scope by 2025.

-

-

The report contains a fairly detailed proposal for conditions which, if met, demonstrate that the investment target does not meet the MS criteria. Unfortunately, it has been directly acknowledged that verification can be difficult.

Investor clients must be asked about sustainability priorities

The EU’s sustainable finance disclosure regulation SFDR (Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation) now also requires ascertaining investor clients’ sustainability priorities before making an investment decision. The obligation is challenging, as often the client does not recognise their own priorities, and the asset manager may not have a suitable investment product in their range. The EU has not provided precise guidelines, but for the time being also permits different practices. Asset managers must disclose about investment funds, among other things, whether they consider E or S characteristics (Article 8 reporting requirement) and how, and/or whether the fund aims to make sustainable investments (Article 9). The articles are not sustainability labels but describe what must be reported to justify sustainability marketing. The role of supervisors is important to prevent overreach.

The key metrics of the EU regulatory package are the so-called principal adverse impact indicators, or PAI indicators, which asset managers are already beginning to report, as well as funds’ taxonomy alignment.

For example, an equity fund has a total of 14 PAIs, of which 9 measure environmental factors and the rest measure social factors and good governance. The indicators are familiar from before, examples being carbon intensity and norm violations. There are 46 voluntary indicators (22 environmental and 24 social). Data on these will become available when companies report on them next year. Data is therefore already available, but coverage across all indicators is not yet high.

ESG data register under preparation

The EU plans to establish the European Single Access Point (ESAP) ESG database. ESAP will primarily provide EU companies and the investment industry with the long-awaited “single window” function. Member states reached agreement on the Council’s position at the end of June. Discussions in the European parliaments are still ongoing. The plan is for the first data to be available by the end of 2026.

Intensified supervision targeting ESG raters, asset managers and banks

Pressure is growing to officially examine ESG rating data providers. In the EU, there are approximately 59 ESG raters, in addition to a few large raters outside the EU.

A negative example of ESG rating is the Indian company Adani Ports, whose business is the transport of coal. The company has been included in, among others, MSCI’s and FTSE Russell’s ESG indices. Its Carbon Disclosure Project (CDP) score has risen to the second-highest level, B, because the company had begun reporting on its environmental risks. MSCI, for its part, excludes companies that earn revenue from coal production and sales, but not from its transport.

According to EU representative Pierre Bollon, the role of ESG data providers is growing and is already significant in the investment industry. Clients and authorities want to obtain ESG information on investments and funds as part of net-zero efforts. Therefore, rating agencies should be subject to regulation as strict as that for, for example, asset managers, brokers, and exchanges.

According to feedback received by the European Securities and Markets Authority (ESMA), there are also deficiencies in the transparency of rating methodologies.

The British Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) published a report stating that it has a “clear rationale” for regulating MSCI, Sustainalytics, and other ESG data providers. Citing “potential harms,” the FCA said the regulatory request came from market participants (pension funds and banks).

According to commentators, some ESG analysts “assess a considerable number [of companies] for cost-efficiency reasons.” Market participants also questioned the depth of knowledge of ESG rating providers’ analysts. Additionally, respondents warned of “product bundling,” where asset managers are forced to pay a high bulk price for ESG data, even though only a small part of it is used.

Authorities have intensified ESG supervision globally. In Germany, the financial regulator conducted a raid on asset management company DWS in May with a force of 50 people to find evidence of misleading ESG marketing of funds. In the U.S., Bank of America has long paid a lower income tax rate than its competitors, only 10%. It has utilised ESG tax credits arising from investments in affordable housing and renewable energy. Otherwise, the tax rate would have been approximately 23%. The matter is under investigation and is an example of ESG- and climate-related inquiries sent by supervisors.

During the financial crisis in 2008, I wondered who supervises credit rating agencies. Now the wondering extends to ESG raters. Although the statutory corporate sustainability reporting described above will also improve the quality of information available about companies and thus the quality of ESG ratings.

Models for combining value creation and ESG

The most common question is how taking ESG into account affects returns. Rating scores as company selection criteria are too crude as metrics. Below are three examples of assessing social impact: Is it a coincidence that it is precisely in process-oriented Japan that a ‘hard numbers’ model has emerged, which both investors and companies have begun to use to create investor value? Eisai pharmaceutical company’s CFO Ryohei Yanagi has seen how investors want to see how ESG activities affect the bottom line.

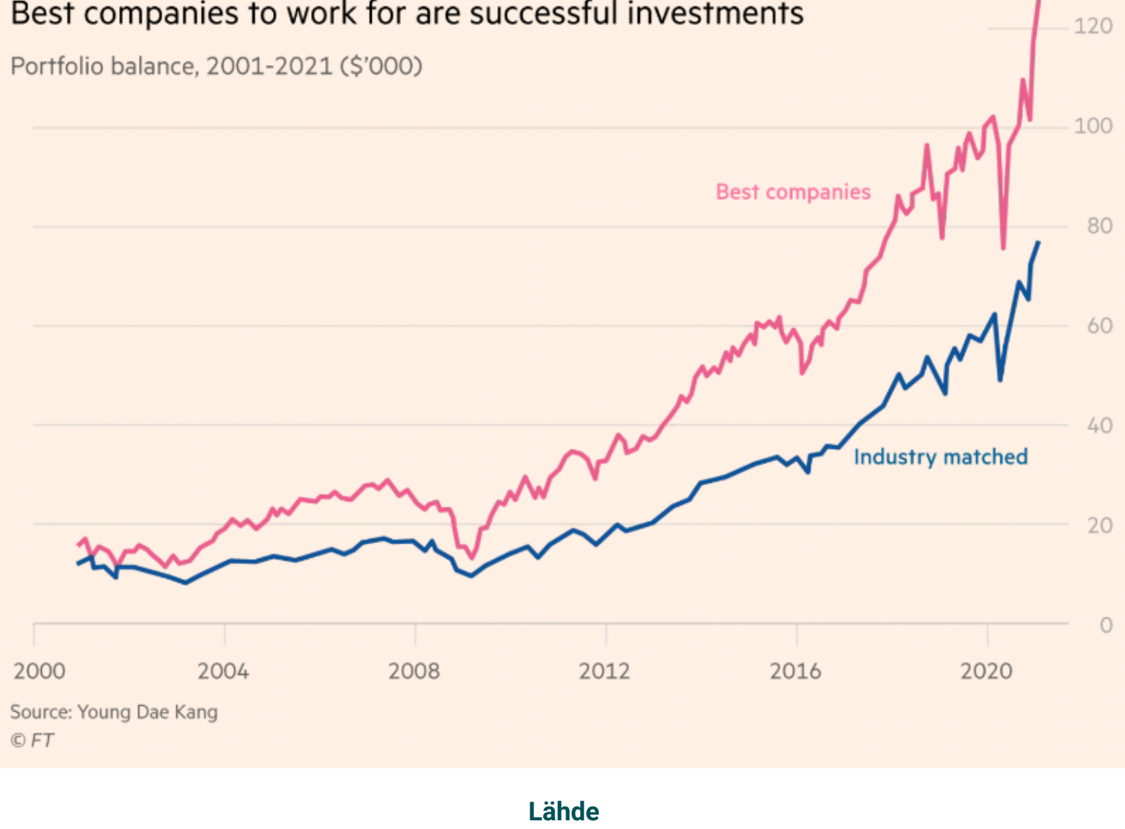

Since 2016, Yanagi has been developing a system that assigns numerical values to 88 different sustainability factors, ranging from the number of maternity and paternity leave takers to the number of employees working abroad and R&D costs. He ran 15,000 simulations with different weightings at his company, using the employer’s share price over 28 years. The results made it possible to link ‘hard’ numbers with ‘soft’ ESG issues and show how investing in personnel and their development through compensation and training increased company value over time. For example, an additional 10% investment in personnel raised Eisai’s comparable price-to-book value by 13.8% over five years. Today, Eisai shows in its income statement how the company’s future value can be increased through ESG activities. NEC, KDDI, and Nissin Foods have now adopted the same model. Yanagi also believes the results will interest BlackRock and other asset managers. Thanks to the standards described earlier, information on sustainability factors will begin to be obtained more broadly. A recent updated global study proves that employee satisfaction and excess returns go hand in hand. When a portfolio is constructed with equal weighting of companies that employees consider to be the best employers, the return premium exceeds 2% per year.

A study published last year found that the disclosure of financially material ESG information affects share prices, especially if the information is positive and even more likely if it relates to social ESG factors.

How to practically direct investments to sustainable targets?

I often hear from the management of investor institutions and investment committee members how difficult it is to standardise asset managers’ reports for setting sustainability targets and monitoring results. This can even be an obstacle to diversifying asset management across multiple asset managers. However, sustainability aggregate reporting deeper than ESG ratings has been possible since the EU’s SFDR disclosure regulation came into force in March 2021. Investment firms already report on sustainability risk management, what E and S characteristics they and their managed funds promote, and how funds’ PAI indicators are developing. According to current information, taxonomy alignment reporting will be included next year. For direct, listed European investments, corresponding information is relatively easy to obtain.

The EU’s mandatory legislation for investment firms (SFDR, including taxonomy) and the forthcoming sustainability standard linked to IFRS are, in our view, a good basis for reporting. The coverage of sustainability data in the report will improve as more companies come under reporting requirements. However, this takes time, and until then one must live with data gaps — it is worth preparing for changes in portfolio sustainability results as more data, including negative data, becomes available. An institution can focus its monitoring by choosing its own adverse sustainability indicators based on the institution’s values and purpose, for example using the principles of the UN Sustainable Development Goals it has selected.

For alternative investments, more manual work is needed, but this also reveals industry-specific sustainability risks and their causes. Company-specific information based on something other than estimation should be available from private funds at the latest in the coming years.

The sustainability aggregate reporting of a portfolio can therefore be divided as follows:

- EU statutory sustainability information: global sustainability risk description (including the largest investments from a sustainability perspective), monitoring of the avoidance of selected adverse sustainability impacts (such as financed emissions and social injustice), promotion of sustainability (taxonomy alignment)

- Other material sustainability information (share of controversial industries, etc.)

- Engagement-related information: potential impact on UN Sustainable Development Goals, screening, direct and indirect stewardship, and governance

How to proceed with statutory reporting in practice (in-house or outsourced):

- Compile the information reported by asset managers on, among other things, sustainability risk management and sustainability implementation (general meeting activities and other engagement) in as standardised a format as possible for comparing asset managers

- Compile the necessary information from asset managers’ statutory reports, with emphasis on sustainability data coverage

- For those asset classes for which statutory data is not yet available, require asset managers to provide the main industry classification of investments for assessing sustainability risks

- Collect taxonomy data on investments where possible

- Gradually extend the assessment to alternative investments

Since information on different asset managers’ investment products, especially structured products, is still quite incomplete, one should be prepared for the report to be supplemented as the amount and reliability of data improve. It is important to ensure that the management and board of the investor institution have sufficient information on what sustainability and engagement targets can be set and monitored.

Summary

In response to the criticism at the beginning, I raise two themes that start from the question: do we, politicians included, have a wrong understanding of what ESG means?

One-sidedness: Investors, especially retail clients, invest sustainably because they want to preserve the planet. However, the ESG ratings behind the selection of ESG funds are based on “single materiality,” meaning the impact of a changing world on a company’s profits and losses, and not the other way around. They have no connection to planetary boundaries. According to Bloomberg, ratings mainly measure the world’s potential impacts on companies and shareholders. Sustainable investing should be based on ‘double materiality,’ where the company’s impact is also taken into account (source).

Choice of metrics: The ESG investor’s focus should be on integrating environmental, social, and good governance risks into the investment process. ESG factors are just one element in an investment process that begins with allocating assets across different asset classes. Instead of crude estimates, for us at Tracefi, sustainability means developing and using industry-specific, ideally science-based, statutory sustainability metrics to create investor value. These are used to find companies that develop products and services to solve our planet’s problems. Regulation is now finally bringing more precisely defined metrics. Investors can take responsibility for implementing sustainability by setting engagement targets and using metrics to monitor asset managers’ actions.

As an example of concreteness, consider the versatility of the SASB ESG metrics framework for the oil and gas industry. The industry itself is divided into four:

-

Exploration and production

-

Midstream (distribution)

-

Refining and marketing

-

Services

Each sub-industry has multiple ESG factors that affect the risk and earnings potential of companies operating in them (Source).

Inequality, like climate change, can be classified as a systemic risk. It is hardly desirable for a company to seek the most favourable location in terms of income and total taxation while not allowing employees to organise (e.g., Amazon), not to mention allowing human rights violations in its operations. Sustainability reporting reforms will in future require companies to report more on their formal processes for avoiding human rights and labour violations, as well as any identified violations (court-confirmed judgements) against these. These, in turn, can be converted into so-called social norm violations, which are already included in the EU’s list of mandatory reportable adverse sustainability indicators.

The tightening of supervisory oversight has a positive impact. It forces asset managers to manage sustainability metrics. The ESG conceptual world is not easy, especially when some concepts have multiple definitions, which the convergence of standards described above is eliminating.

The decision in principle to establish an ESG data register is important. It will lower asset managers’ administration fees and undermine the pricing power of ESG data providers.

News from Tracefi

Our other co-founding shareholder, Mikael Niskala, has sold his company focused on corporate sustainability validation and its business to PwC and will transfer to PwC as a partner as part of the transaction. He will remain a shareholder in Tracefi Oy and will become a member of the Advisory Board to be established. We wish Mikael all the best and believe that he will continue to provide valuable support to our company.

Over the past months, we have been producing SFDR reporting for asset managers and researching best practices in the new reporting from across Europe. At the same time, we have been developing ways to compile sustainability reports for investor institutions that cover all asset classes and the means and monitoring of achieving carbon neutrality. With its concreteness, we hope our customised, heavily regulation-based report will respond to the criticism at the beginning. Autumn begins with training the management and board members of investment institutions on setting targets and directing funds to sustainable targets.

Best regards, Susanna and the Tracefi team

Inspiration:

- Forbes: Professor Bob Eccles’ articles FT: Sarah Gordon: How to make sustainable investing work The Economist: Three letters which won’t save the planet

SASB (Sustainability Accounting Standards Board) is a global sustainability standard that has now become part of IFRS. IFRS (International Financial Reporting Standards) is a financial information reporting framework. ISSB (International Sustainability Standards Board) is a new body driving a centralised sustainability standard. More background here.

Scope emissions contents:

- Scope 1: company’s direct emissions;

- Scope 2: emissions from producing energy consumed by the company;

- Scope 3: value chain emissions, resulting from the company’s activities but from sources the company does not own.

Inspiration:

-

Forbes: Professor Bob Eccles’ articles

-

The Economist: Three letters which won’t save the planet

-

SASB (Sustainability Accounting Standards Board) is a global sustainability standard that has now become part of IFRS.

-

[IFRS (International Financial Reporting Standards)(https://www.ifrs.org/) is a financial information reporting framework

-

[ISSB (International Sustainability Standards Board)(https://www.ifrs.org/groups/international-sustainability-standards-board/) is a new body driving a centralised sustainability standard

-

More background here.