Winter Letter: Time for Action

I aim to share what the autumn has brought investors in terms of sustainable investing. The agenda is therefore:

- Takeaways from the Glasgow summit

- ESG regulation from the investor’s perspective

- ESG also faces headwinds

- New obligations for private funds

- Goal-setting and monitoring - asset class specificity takes centre stage

- Lessons learned by doing

Takeaways from the Glasgow summit

The results from Glasgow highlighted in particular the acceleration of afforestation, ending deforestation, reducing methane emissions, and various levels of carbon neutrality commitments. The negative stance of China, Russia, and Brazil increased the visibility of the USA. While in Paris the participants were largely environmental representatives and scientists, this time the attendees included corporate leaders, financiers, and even finance ministers such as Janet Yellen. Companies actively reported their voluntary measures to curb emissions, some of which had a “business as usual” attitude, and demanded stricter government action to achieve results.

In the corridors, however, there were calls for action rather than just words. There was a demand for commitment to short-term emission targets as well. Thus, the announcement heard at the end of the summit about US-China cooperation to curb emissions already in the 2020s, as well as the general decision on annual monitoring of emission levels, boosted the summit’s optimism. But coal production will continue for a long time, so coal dependency will persist, although the Paris 1.5-degree target was maintained.

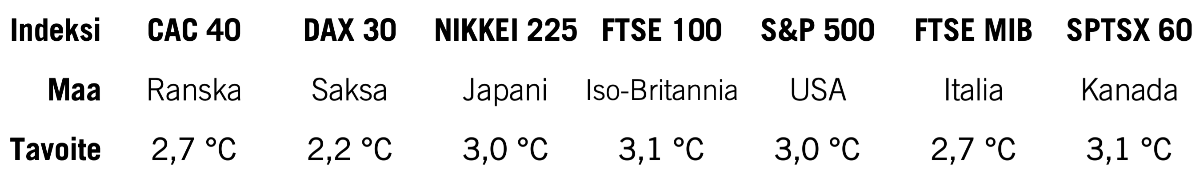

One in three of the G20 countries’ largest listed companies has a net-zero target (Net Zero Tracker), but only one in five of the G20 companies that have set a target has a 1.5-degree target. The actions of investors, asset managers, and banks in redirecting capital flows towards sustainable targets and new technologies are critically important for achieving carbon neutrality. A striking image from an SBT study (June 2021) shows how the vast majority of listed equity investments actually slow down the achievement of climate targets:

The majority of large investors’ portfolios are channelled into the stocks covered by these seven indices. More significant than the degree figures above is, among other things, the information that 70% of Germany’s DAX 30 companies have already committed to the Paris 1.5-degree target, which is already beginning to show as the lowest value in the table.

Among the most prominent initiatives aimed at achieving carbon neutrality are the Net Zero alliances:

- The commitment of global investor institutions to the Net-Zero Asset Owner Alliance, which sets concrete targets for achieving net-zero by 2050, has grown strongly. Already 61 investor institutions have joined the Alliance.

- Approximately 40% of private financial sector actors, i.e. 450 financial institutions managing USD 1,300 billion in assets (the amount may be smaller due to partial double accounting), have joined the new GFANZ (Glasgow Financial Alliance for Net Zero) under the leadership of Mark Carney. (The amount may include overlapping commitments.) The alliance’s initial focus is on the aviation and steel industries.

ESG regulation from the investor’s perspective

European regulators tighten their grip

Due to the EU’s anti-greenwashing disclosure regulation SFDR, which came into force in March, the grip of European financial regulators has tightened significantly. For example, in Finland, a fund may no longer include a reference to responsibility or sustainability in its name without having proven its justification. The disclosure obligation supports the investor’s fund selection, as the fund must declare by the end of 2021 at the latest whether the fund is:

- Article 8 compliant (promotes sustainability themes)

- Article 9 compliant (sustainable investment product)

For the time being, the information is based on fund companies’ self-assessment, until the EU provides more detailed criteria on the subject. This will hopefully happen as early as December.

The years 2022 and 2023 will finally enable investors to look beyond the surface of ESG ratings:

- Investment firms will need to report 18 so-called PAI indicators (Principal Adverse Indicators), which describe sustainability risks and opportunities and are therefore suitable as sustainability metrics. (2022)

- Companies will be required to report on the applicability of the taxonomy to their activities, i.e. whether the company’s activities fall within the scope of the classification system. For activities within the scope of the classification system, the share meeting the taxonomy requirements must then be reported (2022 and/or 2023).

- Based on reported data, it will be possible to determine which listed companies in the portfolio fall within the scope of the taxonomy’s classification system. They have the greatest potential to contribute to the achievement of EU climate and environmental objectives.

- Taxonomy-aligned activity meets the science-based technical screening criteria set by the classification system. That is, they demonstrably contribute to the achievement of EU climate and environmental objectives. The taxonomy criteria are strict, and the requirement is for a significant contribution to EU climate and environmental objectives.

It will be interesting to follow whether Finland will adopt, at least for some actors, the same requirement as in the United Kingdom, where the financial regulator requires investor institutions to conduct climate risk scenario analysis, i.e.:

- sensitivity analysis of different climate scenarios on portfolio returns

- assessment of the economic impact of emissions at various carbon pricing levels.

A new global ESG standard is born

The EU taxonomy and its criteria are already partly known. Now, the internationally recognised financial reporting framework IFRS, whose board of trustees is chaired by Erkki Liikanen, announced in Glasgow that it will establish the International Sustainability Standards Board (ISSB), which the G20 countries welcomed and supported. The goal is to create a single unified baseline standard in the area of sustainable development that meets investors’ information needs. This will help reduce the number of standards and corporate greenwashing.

At the same time, standard-setting bodies and standards will be consolidated. CDSB and SASB will become part of the IFRS Foundation. The standards will be investor-oriented, global, and transparent. The initial focus is on climate, where standardisation can be expected to be open for comment as early as autumn.

The importance of this initiative cannot be overstated. At its best, it will create a global language of sustainability and allow us to go beneath the surface of ESG ratings by learning the financially material KPIs for each industry. Using material metrics, companies can be assessed and concrete sustainability targets set for them.

The road is not easy when politics are involved. The position of the US financial regulatory authority SEC on this initiative is important. As an example of opposing forces: the lobbying power of the coal industry relative to the renewable energy industry is 13:1. Sir Ronald Cohen, who promotes the adoption of impact accounting, refers in his interview to Harvard data showing that, for example, Exxon’s emissions alone cause USD 35 billion in annual environmental damage. Exxon demonstrably lobbies against a carbon tax. Let us hope for rapid progress for the IFRS initiative.

For the Tracefi team, the IFRS initiative is particularly important because we were the first actor in the Nordics to license the SASB standard back in 2017. We chose it because we believe in transparency and facts.

China follows the EU’s path

China, which has been building its green taxonomy together with the developers of the EU taxonomy, has announced jointly with the EU that its taxonomy will follow the EU taxonomy and that development work will continue together, including on green bonds and low-carbon guidance.

ESG also faces headwinds

“Don’t ESG investments actually perform better after all?”

ESG funds and indices typically invest in growth companies and technology while avoiding oil and gas companies as well as basic materials producers. The values of these investment instruments rose strongly in recent years, partly due to falling oil company and commodity prices. During 2021, however, energy company valuations have risen due to strong global growth. Oil companies’ investments in renewable energy technology have clearly boosted the valuations of the technology companies developing them. Among energy companies, the strongest risers are those with a clear transition plan, such as Fortum, which is also affected by the EU’s potential future decision to include nuclear power among sustainable industries. Funds that exclude energy companies have suffered from this exclusion in terms of short-term returns.

Some Human Capital-focused indices have performed well this year. Examples of strong performers (as of 31 October 2021):

- The Morningstar Minority Empowerment Index +38%

- Morningstar Women’s Empowerment Index +37%

These indices were also more heavily weighted in energy and less in technology than many other ESG indices. Technology companies have generally not been exemplary on equality-related issues.

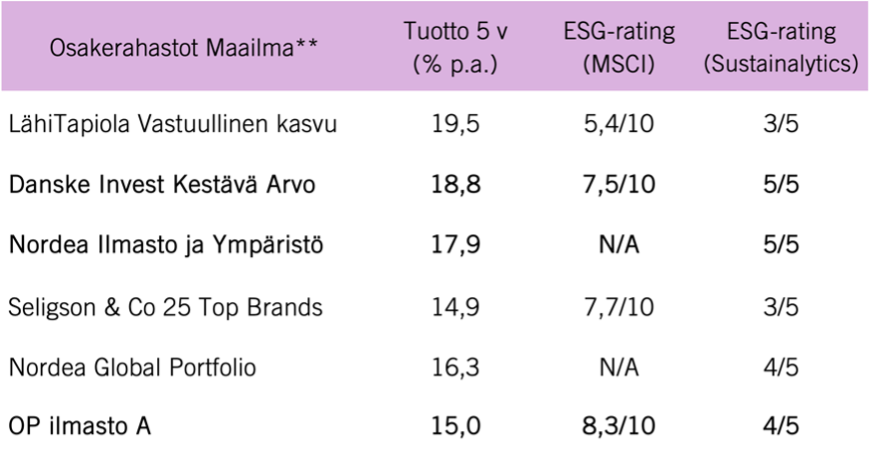

The best performers over a five-year period among the 250 global World equity funds registered in Finland are those where sustainability is primarily based on fundamental analysis, including financially material sustainability topics for their industry. They have clearly outperformed the MSCI World index on an annual basis:

The MSCI World index returned 14% p.a. over the same period.

Whistleblowers have become active

During the autumn, at least three individuals have undermined their employers’ ESG credibility in public:

- BlackRock’s former head of sustainability Tariq Fancy claims in his blog that ESG’s role in investment decisions is superficial and that asset managers like BlackRock primarily pursue returns by favouring ESG. Fancy called for active government regulation to achieve carbon targets. Fancy supports engagement through alternative investments. Could it be partly due to the furore following his blog that BlackRock now allows its largest investor clients direct engagement in annual general meetings?

- DWS’s (Deutsche Bank’s asset management subsidiary) head of sustainability Desiree Fixler accused the company of overly positive ESG marketing and claims that portfolio managers have outsourced the sustainability assessment of investments and thus the responsibility for assessment from DWS without informing clients. Fixler was dismissed. DWS’s share price dropped more than 10% as a result of the scandal. German and US financial regulators are investigating the matter. DWS is not the only asset manager believed to operate in this way.

- The term “ESG integration”, which frequently appears in the investment process descriptions of asset managers and investor institutions, has finally started to raise questions about what it actually means in practice. Many large actors have removed the term from their rules or more precisely defined how sustainability is taken into account when making investment decisions.

- The accusation by former Facebook product manager Frances Haugen targets the company’s pursuit of profit at the expense of its users’ mental health, which from a sustainability perspective is questionable at best. Facebook is often one of the largest holdings in ESG indices.

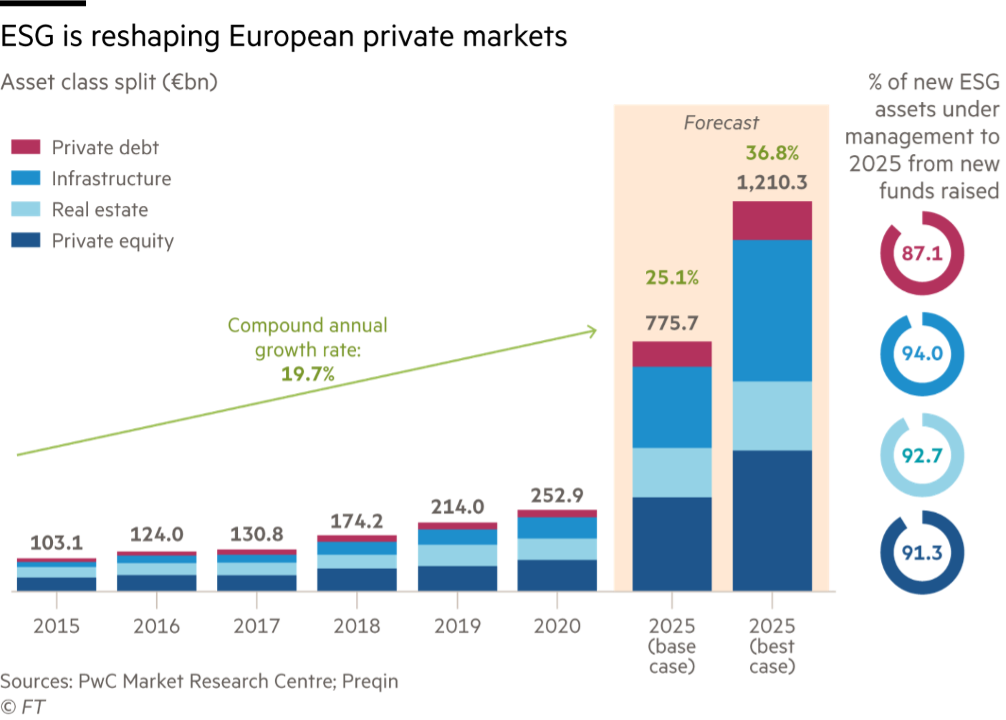

New obligations for private funds

Alternative investments are expected to grow at a 20% annual rate in Europe, and the majority of them have an ESG focus. The share of alternatives in investor institutions’ portfolios is becoming significant. In order to assess portfolio sustainability risks, data coverage needs to increase.

|

|---|

| Source |

Until now, investors’ attention has focused on listed securities and funds. Now two prominent figures, Generation’s chairman Al Gore and BlackRock’s CEO Larry Fink, are strongly demanding transparency from unlisted companies and thus from private equity and private debt fund managers.

Fink warned that pressure directed only at publicly listed companies to produce net-zero plans, while unlisted companies face no equivalent pressure, represents the best opportunity in capital markets to make a profit without risk in his lifetime (arbitrage). Transferring carbon risk to private actors will not change the world, according to Fink.

Gore demands transparency so that asset managers, when cleaning their funds of carbon-intensive companies, do not simply transfer them into the portfolios of new owners in the shadows. At the same time, he called on investors to take action to reduce carbon risk rather than offsetting their emissions.

Practical experience: The work we have done at Tracefi to determine the actual contents of our clients’ portfolios has shown that Fink’s claim holds true:

- Private funds: If we can access the individual sectors and even company names within the funds, we can identify the sustainability-related risks and opportunities in the portfolio and significantly increase the coverage of the analysis. Sector-level portfolio information alone is insufficient for this assessment.

- We cannot assess carbon risk until companies begin to report on it more clearly. In our experience, asset managers’ interest or ability to provide information varies, but it does exist.

- Listed companies: As the break-ups of diversified companies increase, it has become more common to deliberately shift balance sheets to the private capital side to achieve a better rating.

- Corporate bond funds: The issuers of debt instruments are often a financing company within the company’s inner circle, identified only by an abbreviation, from which the company’s true name cannot be determined without further investigation. When the issuer’s background is examined, the share of fossil fuel industries in the portfolio clearly increases.

Politicians are also beginning to demand transparency. The British government announced it would require companies to publish their net-zero plans. This means that auditors will need to include the validation of these plans in their audits. The question is, how?

As an example of the topic’s importance (FT 4 November 2021): an alliance of asset managers overseeing more than USD 4,500 billion in assets is warning Big Four auditing firms that asset managers will not support the appointment of auditors in annual general meetings whose sustainability reporting audits cannot be considered reliable. The ISSB reporting framework described earlier will bring clarity to reporting and report evaluation, eventually enabling such procedures.

There is also dispute about the effectiveness of the emissions offset market and uncertainty about the future of emissions trading. Auditors therefore face a new era and new competency requirements.

Goal-setting and monitoring - asset class specificity takes centre stage

Current practice

For many investor institutions, setting sustainability targets is relatively new. Traditionally, the main focus has been on improving the portfolio’s average ESG rating and being among the so-called best-in-class. E, S, and G dimensions are assessed in silos, even though the sustainability issues that are important to a company actually belong to multiple silos simultaneously. Impact is monitored at a fairly general level; carbon risk and carbon data coverage monitoring is precise for listed holdings, but Scope 3 is missing from assessments. However, for example:

- Microsoft’s head of sustainability stated that Scope 3 will be greater than the company’s Scopes 1 and 2 combined.

- A renewable energy fund may have a high carbon intensity based on Scope 1 and 2. Only when the impact of end products, Scope 3, is included can the positive effect on the entire value chain’s emissions be seen.

The model described above is easy and clear for the user, or is it? Should the focus in sustainability assessment shift from risk management to the return opportunities of the solutions and products produced by the company? Ratings are known to indicate how a company operates, i.e. they focus on processes, and not what products and services the company provides for sustainable development, which is now emerging in taxonomy eligibility assessment. Ratings are good directional indicators, but are currently based partly on analysts’ assessments, until the corporate sustainability reporting obligation comes into force.

What model should replace it?

The UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) are increasingly being adopted as a broader target framework by institutions. Asset managers are also beginning to incorporate them into corporate sustainability assessments. According to Nordea Asset Management’s head of sustainable development Eric Pedersen, the weight of the SDGs in the asset manager’s in-house ESG scoring system is as much as 30%. “In addition to assessing whether companies are conducting good business, we also assess whether they are conducting valuable business, whether they are finding products and services that enable sustainable development.”

The institution’s challenge is to select the SDGs relevant to it. One approach is to compare the sub-targets that companies can influence with the institution’s mission and values. The SDGs were originally designed for nations, meaning that in reality there are considerably fewer sub-targets applicable to companies, as one example below illustrates:

Asset classes in focus

An asset class-specific approach brings concreteness to sustainability assessment, goal-setting, and monitoring. In this case:

- the assessment genuinely starts from the institution’s portfolio,

- each asset class (listed equities, unlisted, etc.) is at a different stage in terms of data availability, so the depth of analysis and ability to influence varies,

- interim targets can be set that reflect the possibilities for influence,

- one asset class at a time can be brought into focus.

The approach described above does not eliminate the need to see the big picture of how sustainability assessment is progressing in the portfolio and what the trajectory of development has been and is.

Briefly on monitoring

Target monitoring must be concrete. At its best, the sustainability metrics being monitored allow access to the investments themselves, the funds containing them, and the asset managers managing those funds, so that conclusions can be put into practice. That is, redirecting capital when needed. Sustainability has now become a strong factor alongside the previously used return/risk ratio and the replacement of portfolio managers.

Lessons learned by doing

The taxonomy has generated considerable work over the year; we have assessed the taxonomy eligibility and alignment of both companies and investor institutions’ portfolios.

In the autumn, we completed an interactive, digital training programme aimed at the management and boards of investor institutions on the topic: “How to allocate capital to sustainable targets.” The pilot group consisted of members of the Finnish Foundations and Funds Association. We were deeply impressed by the positive feedback, which highlighted the training’s clarity, structure, concreteness, and usefulness. We are happy to organise customised training sessions on our subject, now drawing on our experience. The structure of the training was based on:

- an investment process based on the TCFD climate reporting framework (good governance, strategy, risk management, targets and metrics)

- assessment of the sustainability and impact of the institution’s investments by asset class

- assessment of taxonomy eligibility of investments; a topic that should be incorporated into risk management and the identification of return opportunities.

To assist in defining investment policy, we have created an automated tool that can compile sustainable investing principles into a statement tailored to the user’s preferences.

From our team, Mikael has been working in Brussels as an expert for the EU’s EFRAG, designing the content of corporate climate reporting.

We have validated the impact and sustainability of investment portfolios, examining all asset classes where possible and compiling conclusions based on the institution’s objectives.

I was recently asked how we would create a net-zero plan. A net-zero target is included in SDG 13, which aims for climate action and focuses on emission reduction. I replied that the task is not easy and requires a great deal of work. The work starts with an assessment of the portfolio by asset class, i.e. data collection and analysis, selecting interim targets and metrics, and organising the project. We will therefore return to this topic.

We look forward with optimism to next year, when sustainability data will be more readily available and capital allocation can be better based on facts. We want to be your support in that work.

Susanna Miekk-oja and the Tracefi team

SBT (Science Based Targets) initiative encourages companies to commit to science-based targets to reduce their emissions. The driving forces behind SBT are the UN Global Compact, WWF, and CDP (Carbon Disclosure Project).

CDSB (Climate Disclosure Standards Board) is a non-profit organisation, with members including CDP, the World Economic Forum, and other umbrella organisations.

Scope emissions contents:

- Scope 1: company’s direct emissions

- Scope 2: emissions from the production of energy consumed by the company

- Scope 3: value chain emissions, resulting from the company’s activities, but from sources the company does not own