Winter Letter: ESG Finally Moving Toward Concrete Action

Greetings!

One of the feedback comments from our previous client letter was: There are more questions than answers, and the main question is where to find answers. We now aim to focus on answers – how to advance on the ESG path with tangible results.

The topics are:

- Demand drivers

- Once more – is the return on ESG investments on a sustainable footing?

- ESG reporting framework and alphabet soup becoming clearer

- New metrics for the Human Capital area

- More detailed fund evaluation needed

- Models for setting targets and assessing target achievement

- The rise of impact – how?

- From theory to practice

Demand drivers

From January to November 2020, investments in sustainable investment targets grew by as much as 98% compared to the full year 2019. The reasons include strong demand for ESG funds and the trend toward fossil-free investments. The valuations of oil companies and companies with deficiencies in supply chain management collapsed. Genuine ESG funds avoid oil companies and companies exploiting questionable supply chains, and they benefited from this. According to the world’s largest asset manager, BlackRock, more than half of investments will be directed to sustainable targets over the next five years.

The dominance of oil and coal is crumbling:

- Fossil energy sources account for 85% of energy consumed. Energy represents two-thirds of greenhouse gas emissions.

- The share of solar and wind energy is expected to rise from the current 5% to 25% by 2035 and to 50% by 2050. During the transition phase, the share of natural gas, the cleanest fossil energy source, plays an important role.

- The USA intends to invest 2 trillion dollars in reducing carbon dependency.

- The EU has earmarked 30% of its COVID-19 rescue plan’s 673 billion euro budget for climate action and plans to cut greenhouse gas emissions by 55% by 2030 (compared to 1990 levels).

These are better news for both human health and political and economic stability, especially if China stays committed to becoming carbon neutral by 2060.

Geopolitical risks:

- China already produces over 70% of the world’s solar cells, nearly 70% of its lithium batteries, and 45% of wind turbines.

- China also largely controls the rare earth metals needed for clean energy production.

New is the instrumental value of investment instruments in geopolitics: The investment community has largely focused on assessing the impact of climate change on the valuations of bonds and shares issued by private companies. However, over 70% of fossil fuel reserves are held by states, not private companies. Climate change has a significant impact on national economies and their creditworthiness. BlackRock recently launched a sovereign bond ETF weighted toward climate risks, in whose underlying index the share of countries like Germany, the Netherlands, and Spain is small due to their high carbon dependency. By contrast, France’s weight is 34.9%, compared to 25.8% in a traditional index where share size is determined by the size of sovereign debt.

Finland’s share in the index nearly triples to 4.2%. If investing in such indices becomes more widespread, they could have an indirect impact on countries’ financing costs. For Finland, this could potentially reduce financing costs.

A new risk parameter has thus emerged for sovereign bond investors, and its significance in the portfolio is worth assessing.

Once more – is the return on ESG investments on a sustainable footing?

Among the Financial Times’ 10 most-read articles of 2020 was Robert Armstrong’s “The Fallacy of ESG Investments.” The article’s popularity reflects the large number of skeptics.

The author highlights the large share of technology companies in ESG funds and asks what happens when these stocks eventually decline. Does this mean that the ESG profile is a poor investment profile? He also supports the stance described in the headline by citing losses he incurred because he had stuck with value investments after the financial crisis, when growth stocks began to rise. The author therefore warns against believing in investment “isms,” which he also counts ESG as. According to him, excluding sectors cannot carry far because the controversiality of sectors changes over time.

The author fails to consider that sectors differ from each other and ESG issues are strongly sector-dependent. He also does not pay attention to the financially material ESG issues within each sector. Yet these are precisely what research has shown to be the foundation of sustainable returns in ESG investing.

The domestic December 2020 Fund Report states that of the six best-performing global equity funds over a five-year period, five are genuine ESG funds where the focus is on incorporating ESG into investment decisions. They have portfolio managers specialized in ESG issues and are often small funds – in larger funds, in-depth analysis of companies is more difficult, and assessments are often based on coarser quantitative analysis.

ESG reporting framework and alphabet soup becoming clearer

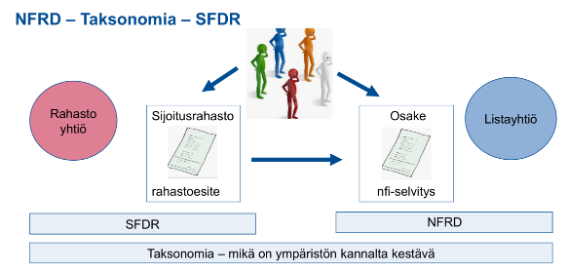

EU guidance is being implemented. For providers of investment products, SFDR (Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation) Level 1 disclosure obligations come into force on March 10, requiring providers to report on sustainability-related risks of their products. Providers must also report on how sustainability consideration in investment activities is reflected in the service provider’s remuneration.

On Thursday, February 4, the EU Commission received from the European Supervisory Authorities (ESA) a draft of Level 2 Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation (link) Regulatory Technical Standards (RTS). This draft standard contains technical guidance on the content and scope of required sustainability disclosures, their calculation methodologies, and reporting. The Level 2 requirement will likely come into force by the beginning of 2022.

By January 2022, an obligation to report the percentage share of investments meeting the EU taxonomy criteria and the shares of enabling activities and transition activities in investments is expected to come into force. The first phase of the taxonomy concerns climate change-related factors.

Investment service providers must report from March onward to the best of their ability, even though the regulatory details are not yet fully clear.

|

|---|

| Image from the Financial Supervisory Authority’s seminar on November 27, 2020, “Trends in Sustainability Reporting,” whose materials are worth reviewing. |

EFRAG’s (European Financial Reporting Advisory Group) expert group, responsible for EU standards, has spent the past three months planning the structure of the corporate NFRD (Non-financial Reporting Directive) content for further action. The group’s only Finnish member has been Tracefi Oy’s founding partner Mikael Niskala. Key themes that emerged during the planning include the importance of defining the materiality of sustainability issues, the sector-based approach, and SME reporting.

Future corporate reporting and the new asset manager reporting will enable investors to set targets on various sustainability issues. The asset manager reporting obligation aims to reduce the share of greenwashing and SDG-washing in fund offerings. The change in reporting will be very significant – focusing on ESG ratings alone will no longer suffice; reports must be based on sustainability data.

Different ESG standards are converging, and may merge. The biggest change is the USA’s return as a supporter of climate change mitigation and adaptation. This facilitates the creation of a global ESG standard. President Biden has just appointed Gary Gensler, considered highly effective, to head the top securities regulator SEC, though he has not yet expressed his position on corporate climate reporting. Brian Deese, BlackRock’s former head of ESG policy, has been named chief economic advisor to the White House.

What is new is that the IFRS (International Financial Reporting Standards), the global framework for all financial reporting, is considering the formation of a body called SSB (Sustainability Standards Board) aimed at integrating sustainability standards alongside financial reporting. Hardly any larger company could imagine operating without IFRS as the basis of its financial reporting. Bank governor Erkki Liikanen serves as chair of the board of the global IFRS Foundation. IFRS is renewing its strategy and has surveyed various market participants and regulators on whether it should establish the SSB. If the answer is positive, preparatory work on developing common standards will accelerate. Environmental reporting is likely to be the first topic addressed.

Five sustainability standards – GRI, SASB, CDP, IIRC, and CDSB – recently published a new type of reporting prototype based on TCFD climate reporting as a basis for the IFRS work.

The significance of this matter is demonstrated by the fact that the leaders of three major financial industry players – Bank of America, State Street, and BlackRock – jointly expressed their support for the IFRS initiative (SASB seminar, December 1, 2020). At the same time, they clarified the ESG alphabet soup by emphasizing the importance of three entities: IFRS, SASB, and TCFD for the investment community. The SASB standard is supported by its sector-based approach and investor orientation. The UN also supports the IFRS’s role as a unifier. It is possible that we will hear already in March whether IFRS will accept the important challenge of building a global ESG standards framework.

New metrics for the Human Capital area

A recent study, Test of Corporate Purpose, examining 800 globally listed companies, shows that companies that have performed best in managing financially material ESG issues have also performed best during the COVID-19 pandemic. These companies also have their human resource management in order. Institutions and asset managers have now increased the weight of the S – social topics – in ESG factors.

SASB has had a project underway for over a year to update Human Capital reporting topics and metrics and to increase their weight relative to all sustainability topics. The proposal is open for comment until February 12, 2021. The major trends behind this include automation and technology, growing income inequality, globalization, and changing workforce demographics.

As industries shift from production-oriented to service-oriented, the need for the ability to utilize knowledge grows and work quality is emphasized. The new human resource management themes are then:

- Workplace culture and empowerment opportunities

- Employee well-being and occupational health care

- Supply chain working conditions

- Workforce skills development and wealth building (e.g., retirement savings)

- The role of alternative workforce, freelancers, and temporary workers in business strategy

These topics will generate new reporting themes alongside current topics such as working conditions, diversity, and employee turnover. Personnel funds permitted by Finnish legislation are at their best a channel for employee empowerment and retirement savings. If SASB selects the above themes for measurement, institutional investors will likely reward companies that have a personnel fund in place. The launch of new metrics is expected during the current year.

More detailed fund evaluation needed

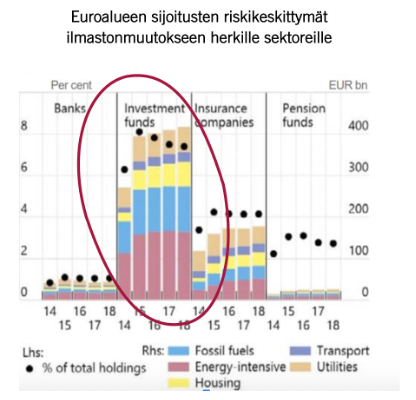

The majority of institutional investors operate with very limited human resources, making fund investing understandably the main channel for global investing, especially in emerging markets. The Financial Supervisory Authority highlighted the severity of climate risk hidden in funds using the image below. If fund contents are not analyzed more closely, several climate risk exposures may go unnoticed. ESG ratings and carbon footprint measurement alone are not enough, especially as long as carbon risk focuses only on the assessment of Scope 1 and 2 emissions. The expanding requirement to also report Scope 3, i.e., emissions generated by the users of companies’ services, particularly affects internet and technology companies.

When reading fund investment policies, one BlackRock ETF comes to mind whose investment policy carefully described the ESG rating and carbon risk but added that these factors do not influence the ETF’s investment choices unless specifically mentioned.

ESG ratings are good assessment tools, especially for evaluating direction, but they are not sufficient. According to the ERM SustainAbility Institute’s Rate the Raters 2020 study, institutional owners use more than one rating. We have developed a method for examining fund portfolio contents and use Sustainalytics’ ESG rating for funds. We utilize this method in evaluating asset managers. The SFDR reporting package mentioned above will facilitate evaluation, at least for European funds.

It is worth investigating what kinds of funds, particularly index funds, the portfolio contains. The task is not easy – there are already over 1,000 different ESG indices.

Models for setting targets and assessing target achievement

Institutions are increasingly interested in the evaluation of investments from an ESG perspective as a return driver, in risk management, and in terms of impact. Mere numbers and ratings are not sufficient for evaluation; there is also demand for conclusions.

The TCFD climate reporting model, where climate topics are addressed through governance, strategy, risk management, and metrics and monitoring, is likely to be applied to other ESG areas in the future as well. We have found that this structure works well as a framework for sustainable investment principles.

The climate theme is currently at the center of attention for many due to its urgency. The increasingly common practice of monitoring carbon intensity and comparing it to a benchmark already tells a lot. Although Scope 3 emissions are still often missing from monitoring. The assessment of corporate bonds has also received little attention, even though they often contain bonds from fossil-intensive companies. We have sought to find a solution for this. We have not yet seen the use of low-carbon benchmarks by anyone other than international institutions; they are likely to first become common as a product and then as part of a benchmark.

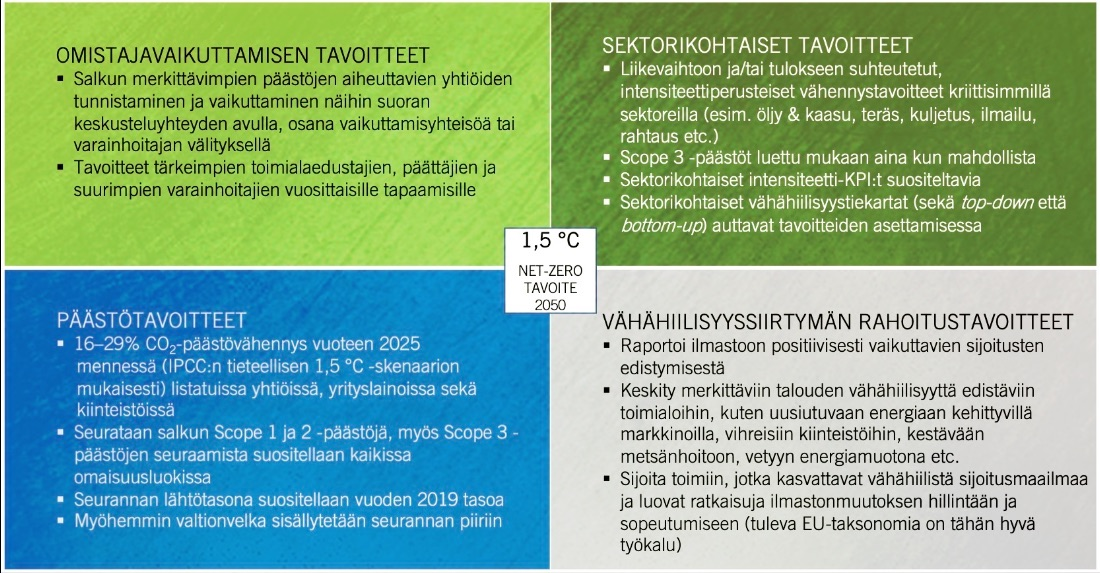

Asset owner institutions’ commitment to achieving carbon neutrality

In December 2020, approximately thirty significant global investors (Allianz, Fidelity, Nordea Pension, CalSTRS, etc.) announced as an alliance the Net Zero Target, which is a concrete commitment to achieving carbon neutrality by 2050. There are numerous different commitments, but this one caught my attention because one of its initiators is David Blood, founding partner of Generation Investment Management. Generation is the first asset manager I know of to have integrated ESG well into its investment process.

The alliance relies heavily on the Science Based Targets sustainability framework, to which committed companies set goals for achieving the Paris climate targets and report on their progress. The alliance intends to influence companies directly or through its asset managers, and does not rely on ESG ratings from external parties. The commitment’s sub-targets (pdf) are, in their concreteness, highly useful for planning climate-related target setting for other institutions as well (click to enlarge):

The rise of impact – how?

Engagement by asset owner institutions with companies, either individually or collectively, is on a strong rise globally. Engagement is also a way to protect against the systemic risk of inequality, in addition to climate change.

The traditional form of engagement is exclusion, where the focus is on avoiding violations of UN norms. Exclusion and screening have gained a new dimension, for example through the exclusion of carbon-intensive sectors.

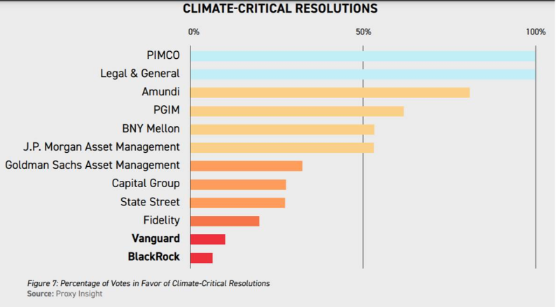

One means of engagement is to favor asset managers that influence companies in line with the institution’s own objectives. Large asset managers have the power to require companies significant to climate change to make the decisions that the climate crisis demands. Below is a perhaps surprising table from the Majority Action 2020 report on how little the large asset managers BlackRock and Vanguard used their voting power to influence the actions of corporate boards:

This may be changing: In BlackRock’s 2021 client letter, the CEO emphasizes the opportunities of net-zero emissions for investors and commits to publishing a temperature alignment metric for tracking climate targets in public fixed income and equity funds, once reliable data is available. At the same time, it requires the companies it invests in to report on how they will achieve the Paris climate targets and reach carbon neutrality by 2050.

One way for institutions to retain their influence or that of their asset manager is to prohibit the custodian from using their shares for securities lending on the record date of the general meeting. Index investors often surrender their voting rights; large investors have the opportunity to try to influence index fund asset managers directly.

One enabler of the low costs of index investing is the revenue stream from lending securities held in custody by index fund asset managers. It depends on the service providers whether part of this revenue stream flows back to the fund’s unit holders. Investors should investigate their asset manager’s lending practices.

The use of the UN Sustainable Development Goals as a roadmap for engagement has begun. This starts from the institution’s own sustainable development goals and influences targets through its own operations as well as through investments, by defining practical measures and KPIs.

An increasing number of institutions are implementing impact through alternative investments. For example, private equity and private debt investments, either through fund structures or directly, are a transparent way to exercise owner influence through board work or otherwise.

From theory to practice

It is evident that sustainability has a long-term impact on returns and that an investor institution can also exert influence by allocating investments. How each entity operates is individual and requires in-depth reflection by management and the board, for example through the following questions. Target setting always starts from the asset owner institution’s identity and objectives, as well as understanding the starting situation:

Institutional identity

- Purpose, values, roles, and responsibilities

Institutional impact

- Is there reason or opportunity to select the institution’s own UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)?

- If yes, what are they?

- What means of influence are used to achieve the targets (directing grants, own operations, directing investments)?

- Exclusion and/or screening principles and favoring (UN norms, sectors)

- Index selection (as investment targets or benchmarks): use of low-carbon benchmarks?

The institution as owner

- Should the institution be an active owner? If yes, how is the intent documented? What are the measures and channels and forms of engagement? How are asset managers instructed on the topic? And monitoring?

The institution as operator

- Are the portfolio’s sustainability exposures, i.e., risks and opportunities related to sustainability issues, known for assessing the starting situation for target setting? If yes, are sustainability-related risks diversified?

- What is the coverage of sustainability data by asset class? Is coverage developing favorably?

- Is capital being directed purposefully to sectors and/or geographic areas that seek to find solutions to the institution’s chosen targets?

Examples of climate-related questions:

- Has a carbon neutrality target been set? If so, is the target year 2030, 2035, 2050, or another?

- Have medium-term, concrete targets been derived from this that are monitored?

- Are the economic impacts of climate change known and how is the portfolio positioned relative to the Paris targets?

- Use of low-carbon benchmarks as part of the institution’s base allocation?

- Is the portfolio’s distribution according to the EU taxonomy’s so-called low-carbon enabling sectors and transition sectors known?

We are happy to participate in concrete target setting and ensure regular assessment of results, including asset manager comparison. Integrating sustainable investment principles into the investment strategy, starting from the answers to the above questions, among others, is a good roadmap for progress.

We strengthened our capital structure at the end of the year, and Jonas Palmen joined our team of six, taking on roles in sustainable finance. Jonas joined us at the beginning of January from Miltton Markets, and he wrote his master’s thesis on evaluating the performance of Nordic companies using SASB.

We added CUSIP (fixed income data, USA, Japan, Asia) and Morningstar Direct for fund monitoring alongside SASB as data sources.

Until we meet again, Susanna Miekk-oja and the Tracefi team

- CDP: Carbon Disclosure Project

- CDSB: Climate Disclosure Standards Board

- GRI: Global Reporting Initiative

- IIRC: International Integrated Reporting Council

- SASB: Sustainability Accounting Standards Board