The topics for my summer–August 2019 newsletter are the following:

- A brief guide to taxonomy

- Global progress of ESG: will Japan finally open up to ESG investors?

- Why are ESG ratings not enough for investors?

- Investor stewardship code – is one needed in Finland?

A brief guide to taxonomy

In June, the EU advanced the implementation of its sustainable finance strategy and adopted a recommendation on climate-related issues for companies’ non-financial reporting (NFRD); the reporting recommendation is non-binding. The TEG (Technical Expert Group) published reports on:

- taxonomy

- the EU Green Bond Standard

- climate benchmarks and the principles for benchmark reporting

The taxonomy report provides a framework for taxonomy-related legislation. **Taxonomy is a tool that helps companies and investors determine whether an economic activity is environmentally sustainable. This is the case if the activity makes a significant contribution to at least one of the following objectives, without causing significant harm to the others:

I) climate change mitigation

II) climate change adaptation

III) sustainable use and protection of water and marine resources

IV) transition to a circular economy, waste prevention and recycling

V) pollution prevention and control

VI) protection of healthy ecosystems** The taxonomy is built on top of the EU’s NACE industry classification system. The Finnish TOL industry classification is based on the NACE classification system.

The report provides:

- 67 technical screening criteria for activities that may have climate change mitigation impact across 8 sectors (agriculture; forestry; manufacturing; electricity, gas, steam and air conditioning; transport; water and sewerage; information and communication technology; and buildings and real estate). Nearly every one of these sectors has also been assessed for potential adverse impacts

- a methodology and examples for assessing the significant impacts of climate change adaptation

The taxonomy content will continue to be developed, with plans to expand it to cover more sectors, but it is ready for use now. At its best, the taxonomy gives investors a tool to identify and communicate what proportion of the economic activities of companies in their investment portfolio is environmentally sustainable.

Global progress of ESG: will Japan finally open up to ESG investors?

Two Nordics, a representative of AP4 and the undersigned, joined a large audience in the sweltering July heat in Tokyo at the ICGN (International Corporate Governance Network) annual conference. The participants were predominantly Asian, particularly Japanese and South Korean asset managers and institutional investors. The theme of the conference was steering good governance towards sustainable value creation.

My reason for attending was not nostalgia for familiar surroundings — I had worked there for about three years — but to see how ESG is progressing beyond Europe and the USA. Japan is an important investor influence; its citizens are savings-oriented, making its life insurance companies and pension funds significant in scale — for example, the government pension fund GPIF (assets of USD 1.4 trillion) is the world’s largest pension fund, whose policy directions global asset managers follow closely. Japan’s economy is the third or fourth largest in the world by GDP, as is its capital market, with 3,672 listed companies.

Traditionally, Japanese companies have been extremely reserved in their reporting. The cluster structure of companies has obscured the true ownership base, and the quality of governance has been difficult to assess, not least due to the language barrier. Non-financial reporting by Japanese companies has lagged behind international peers. For example, Generation Ltd., an experienced sustainability investor, has participated in the Japanese market only through derivatives, as the companies’ reporting has not been satisfactory for them.

Japanese companies are considered leaders in innovation and are among the top countries in, for example, robotics for elderly care. This is a skill that Japanese companies will export to other Asian countries whose populations are also aging.

The most striking feature of corporate values is illustrated by an old survey result that likely still holds: 97% of American companies considered shareholders their most important stakeholder, while in Japan 67% regarded employees as the most important. In August 2019, the influential Business Roundtable in the USA strongly called for a more Japanese-style value system for corporations. As the service sector grows, the value of intellectual capital rises. In Japan, as far back as the Edo period (AD 1603–1868), merchants operated on a win-win-win principle, where not only the buyer and seller but also society had to benefit from a transaction.

In Japan, women’s share in the leadership of the top 100 companies is only 6.5%. This figure is rising; Prime Minister Shinzo Abe’s Womenomics program aims to raise it to 30% in blue-chip companies next year. An aging nation needs women not only for bearing children but as part of the active workforce. A surprisingly large number of the seminar participants were women, who also participated actively in discussions.

Japan’s new corporate governance code

In Japan, several ministries have collaborated under the leadership of Prime Minister Abe to develop a corporate governance code, the revised version of which was published in June 2018.

The core of the code is:

- proper consideration and utilization of the cost of capital in resource allocation;

- normalization of the CEO position (a transparent process for hiring and, when necessary, dismissing the CEO based on an assessment of company performance);

- linking executive compensation to medium- and long-term objectives.

Recent symbolically important developments:

- ACGA (Asian Corporate Governance Association) lowered Japan’s ranking among Asian countries from 3rd to 7th, as low as India.

- A US activist fund forced Olympus to appoint foreign members to its board. Olympus agreed to the proposal, marking the first time a Japanese company yielded to an activist’s proposal. Japanese companies have typically refused such proposals or responded with silence.

- At Lixil’s annual general meeting on June 25, 2019, a shareholder power struggle led, for the first time in Japan, to a CEO being elected against the company’s proposal. This signified that foreign investors were dissatisfied with the nomination committee’s internal process and that they prioritized substance over formalities.

Now the focus is on group governance. One of the most important themes is the issue of listed subsidiaries; there are approximately 600 listed subsidiaries. In Japan, the government is also paying attention to this matter, and METI* has just published guidelines on how to curb conflicts between parent companies and minority shareholders through transparent reporting and the appointment of independent board members.

Competitiveness and incentives for sustainable growth through corporate–investor collaboration

Professor Kunio Ito has led a METI project aimed at sustainable growth. GPIF has positioned itself firmly as an advocate for reform. Ito’s presentation was based on the revised governance code described above. According to the project, sustainable growth in a company’s value development can be achieved in two ways:

- Value creation by improving capital efficiency (ROE–ROIC), strengthening the role of the board, and maintaining dialogues with investors.

- Sustainable medium- and long-term value creation by promoting ESG–SDGs (UN Sustainable Development Goals) under TCFD** guidance.

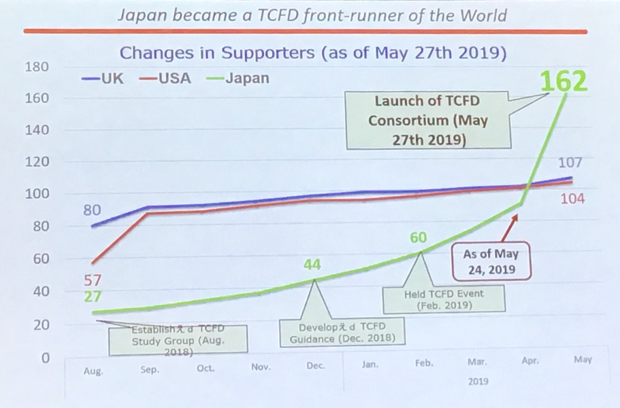

Climate change is the most important of the ESG issues and sustainable development goals. METI has produced guidelines for Japanese companies on adopting the TCFD. The effects are clearly visible. Japan has risen to the top globally in terms of TCFD reporters. The TCFD will gain further momentum at a Summit on the topic in Tokyo in October.

In summary:

- Long-term value creation should aim for both high-quality ESG and high-quality ROE

- In Japan, values have historically been aligned with the SDGs

- Japan is the largest supporter of the TCFD

- Growth in the adoption of TCFD guidance requires strong collaboration between companies and investors.

If Japanese companies put sustainable value creation into practice, this opening up could have a long-term impact on share value development, but also on the value of the yen. After returning home, I asked Generation whether they had now directed investments into Japanese companies. The answer was affirmative, and I learned that Al Gore, who is the chairman of Generation’s board, has been working closely with GPIF’s CIO. I would call this genuine impact.

Why are ESG ratings not enough for investors?

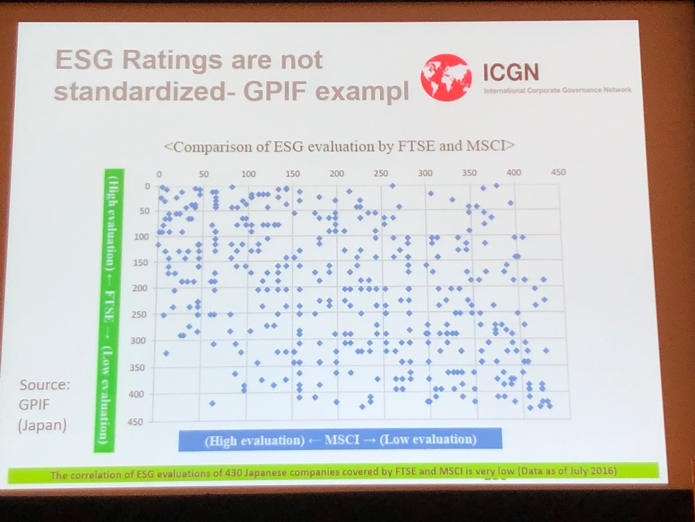

There is a great deal of research on the correlations between different ESG ratings. The general rule is that their methodologies are a “black box” and they do not correlate with each other. At the ICGN conference in Tokyo, GPIF compared the MSCI and FTSE sustainability ratings of 430 Japanese companies. The chart below makes for sobering reading — the correlation is very low:

One of BlackRock’s founders, Vice Chairman Barbara Novick, described investor stewardship codes across different countries. When the discussion turned to the inconsistency of different ESG ratings, both she and the CEO of Ontario Teachers’ Pension Plan spoke strongly in favor of the SASB standard***: “TCFD and SASB are the ones that will survive. SASB because it is industry-based and has a focus on financial materiality.” The head of Nissei Asset Management, shown on the right in the image, also mentioned that the company is a SASB partner.

ESG data comes from everywhere. In the ICGN-organized training “Stewardship and Sustainability,” ESG analyst Kathlyn Collins, representing the US-based Matthews Asia, mentioned that they spend approximately USD 300,000 per year on data sources. Half of the data is collected from public sources and half from paid sources. She also considered SASB the best tool for forward-looking analysis; she followed ESG ratings primarily to determine the direction of trends, considering them too backward-looking.

Investor stewardship code – is one needed in Finland?

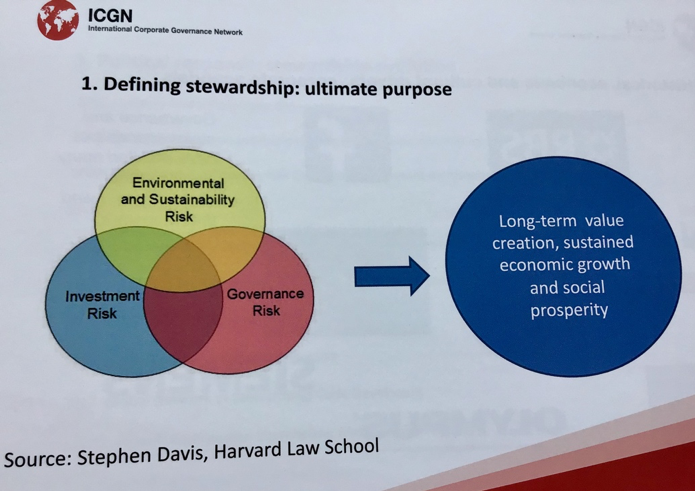

I participated in ICGN’s thorough training, the topic of which was investor and asset manager stewardship codes and how to integrate ESG into investment decisions. The topic is broad. Different countries have their own codes, the most developed of which is the UK code, currently being revised, which has served as the basis for developing codes in many countries. Canada and Japan have also developed their own codes. In Canada, it is being built through collaboration between institutional investors and companies. In many countries, the topic has a long tradition; one of the advantages of a code is that it clearly defines roles and responsibilities from board members to asset managers and provides a framework for both target setting and monitoring.

What stood out in the training was its partly outdated approach, as it did not take into account the TCFD’s forward-looking framework. In Tracefi’s experience, this framework also works well when supplementing investment policies and serves as a useful mirror for the EU’s corporate reporting recommendation. Several large investors from Canada who attended the seminar had reached the same conclusion.

In Finland, it has been customary to document investment, risk and ownership policies, as well as the principles of exclusion and restriction. The question is: is a change needed — that is, should Finland have its own investor stewardship code guidelines? If so, who should be tasked with creating them?

The stewardship code, depicted in the ICGN image below, describes the purpose of the institution and the implementation of fiduciary duty.

The summer brought congratulations from around the world for mentions in the international IRRI (Independent Research in Responsible Investment) Survey 2019 in the category “Most positive contribution to Sustainable Investment.” We received recognition as the only independent sustainability and impact data provider in Finland. The news was heartwarming, and it provides a good foundation to build on.

Solidium’s Investment Director Annareetta Lumme-Timonen, in turn, reached the top ten in the category “Best understanding of companies – asset managers.”

It would be great to receive your feedback, opinions, or information about sustainability topics that interest you.

Best regards, Susanna M.

* Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry, Japan’s Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry

** Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures is a market-driven harmonized reporting recommendation that examines the financial risks and opportunities of climate change.

*** Sustainability Accounting Standards Board. The SASB standard is the only global sustainability standard that bases its methodology on industry-specific financial materiality.